Anna Marie Hennen Hood

Wife of Confederate John Bell Hood

Anna Marie Hennen was born June 28, 1837. She was the daughter of a prominent New Orleans attorney, Duncan Hennen, and granddaughter of Alfred Hennen, Justice on the Louisiana Supreme Court. She was described as beautiful, charming, and she was educated in Paris, France. She wouldn't meet John Bell Hood until after the Civil War.

John Bell Hood was born June 29, 1831 in Owingsville, Bath County, Kentucky. He and his siblings were left with their mother for approximately eight months each year during the middle and late 1840s during Dr. John Hood's annual visits to Philadelphia, where he taught medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. During the extended absences of his father, young John Bell would be influenced by his grandfathers – Lucas Hood, a crusty veteran of the Indian Wars, and his maternal grandfather James French, a Revolutionary War veteran – who engendered his love for the adventure of military life.

Anna Marie Hennen Hood

John Bell was urged by his father to take up the study of medicine, and was even offered an opportunity to study in Europe. But he wanted to follow in the soldier's footsteps of his forefathers, and with the assistance of his uncle, Judge Richard French, he received an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point, enrolling on July 1, 1849.

Many cadets from southern states would struggle academically, due to the general lower quality primary education in rural areas. This may explain Hood's poor academic performance, since he was educated at a subscription school in Clark County, Kentucky. At West Point, his weakest subjects were philosophy and French. His strongest classes were mathematics and drawing, and he ultimately graduated 44th out of 55 students in the Class of 1853, which included Civil War notables James B. McPherson, John M. Schofield, and Philip H. Sheridan.

In March, 1855, at the urging of US Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, Congress authorized the formation of two new cavalry regiments that would protect settlements on the frontier of Texas. The Second Cavalry Regiment at Fort Mason, Texas, would be a virtual who's who of the Civil War.

Its commander was Mexican War hero Colonel Albert Sydney Johnston; Robert E. Lee was the regiment's lieutenant colonel; William J. Hardee and George Thomas, majors; Earl Van Dorn, George Stoneman, and E. Kirby Smith captains. Hood was promoted to second lieutenant of cavalry and reported to Colonel Johnston at Jefferson Barracks in St. Louis, Missouri in October, 1855.

In September 1860, Hood received orders to report to West Point to serve as Chief Instructor of Cavalry. However, at Hood's personal request to US Adjutant General Samuel Cooper, the order was rescinded, and he remained with the Second Cavalry Regiment.

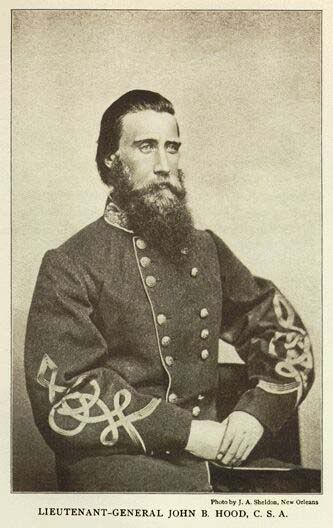

In April 1861, with the outbreak of the Civil War, Hood tendered his resignation from the United States Army and offered his services to the newly formed Confederacy. He was promoted to full colonel, and given command of the Fourth Texas Regiment. On March 7, 1862, he was promoted to brigadier general and placed in command of the Texas Brigade of Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. In October 1862, following the Battle of Antietam, Hood was promoted to Major General at the recommendation of General Lee.

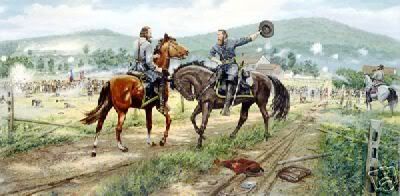

John Bell Hood at Gettysburg

On the afternoon of July 2, 1863, General Hood's division was ordered by General James Longstreet to begin the attack on the Federal defenses on Little Round Top. The Confederates would have to approach the Federals over several hundred yards of open ground, and then assault the elevated Union positions through rough, boulder-strewn ravines.

Brigadier General Evander Law sent scouts around the right side of Little Round Top, and found the rear approaches to the Union positions to be unguarded. Law approached Hood, apprising him of the situation, and Hood agreed wholeheartedly that a flanking maneuver would be more effective, and sent an urgent message to General Longstreet requesting permission to do so. Longstreet refused; Hood appealed to him again via courier.

After Longstreet again refused again, Hood sent his adjutant to implore him to reconsider. Longstreet again denied his request, and ordered him to continue the attack as previously instructed. At this point, Hood personally rode to Longstreet, protested the attack that he was being ordered to conduct. Longstreet, for the fourth time, refused to allow him to attempt a flanking movement.

Hood's Protest

By artist Dale Gallon

Hood began the attack up the Emmitsburg Road as directed. At approximately five o'clock, 20 minutes after the attack began, Hood's left arm was shredded by shrapnel from Federal artillery. He would be taken to the rear, unable to participate any further in the battle. Although his wounded arm would be saved from amputation, it would be permanently paralyzed, and he carried it in a sling for the rest of his life.

The determined Confederate assault on the slopes of Little Round Top was eventually repulsed by the defending Federals; the carnage that Law and Hood had anticipated did in fact materialize.

Hood's division succeeded in removing the Federal troops at the base of Little Round Top, the area that would forever be called Devil's Den, but were able to seize only a portion of the summit of Little Round Top.

For the remainder of the battle, Hood's division held their ground, while on July 3, 1863, Lee's famous assault on the Union center, Pickett's Charge, failed to defeat Meade's Federals. The Battle of Gettysburg ended in a Confederate defeat, as Lee's army began their retreat back to Virginia in a driving rain on July 4th.

During his convalescence, Hood was a hero to the people of Richmond. Confederate authorities sent Longstreet's corps to northern Georgia to assist General Braxton Bragg's Army of Tennessee in halting the Union advance through Middle Tennessee. Hood, recovering from his wound, accompanied the division into Georgia.

On September 18, 1863, Longstreet's corps reached the banks of Chickamauga Creek. The next day, while leading a furious assault during the Battle of Chickamauga, Hood was struck in the upper right leg by a rifle ball, shattering the femur. He was carried to a nearby house with his bloody leg dangling off the side of the litter. Doctors amputated his right leg just below the hip.

Hood was horribly disfigured by the amputation, retaining but a four-and-a-half-inch stump. His great physical strength and will pulled him through the hideous ordeal. Outfitted with a wooden leg, Hood returned to the army.

In less than seven weeks, Hood lost the use of one arm and underwent the amputation of his leg. The injuries entitled him to a medical discharge, but Hood remained in the army and received a promotion to lieutenant general in the Army of Tennessee on February 1, 1864.

He was assigned to serve as a corps commander under General Joseph E. Johnston. Arriving in Dalton, Georgia, on February 4, 1864, Hood served under Johnston throughout Union General William T. Sherman's north Georgia campaign during the spring of 1864. On July 17, 1864, Hood received a temporary promotion to full general.

Throughout the summer of 1864, General Joseph E. Johnston, commander of the Army of Tennessee, had conducted a campaign to slow the advance of General William T. Sherman's march to Atlanta. Disgusted with Johnston's inability to stop Sherman's progress, President Jefferson Davis replaced Johnston with Hood, commanded the defending Confederate forces during the siege of Atlanta, from that time until evacuating the city on September 2, 1864.

In July 1864, when Hood assumed command of the Army of Tennessee, he had more than 50, 000 soldiers. By November, battle casualties had reduced the number to less than 30, 000. Despite a reputation for bravery, Hood's poor understanding of military tactics resulted in a series of crushing defeats to the armies under his command at the end of the Civil War.

On November 19, 1864, Hood's Army of Tennessee left Florence, Alabama, for an ill-fated invasion of Tennessee. On November 30, Hood's forces suffered staggering losses in a decisive defeat at Franklin, Tennessee, at the hands of a Union force commanded by his West Point classmate General John Schofield.

Two weeks later, Hood was routed at Nashville on December 16 by his former US Army colleague General George Thomas. After a humiliating retreat to Tupelo, Mississippi, Hood resigned his command on January 23, 1865, reverting to his permanent rank of lieutenant general.

During the waning days of the Confederacy, Davis ordered Hood to travel to Texas and attempt to raise an army of 25, 000 troops. Learning of the surrender of General Kirby Smith in Texas, Hood surrendered to Federal authorities in Natchez, Mississippi on May 31, 1865.

After receiving his parole, Hood went to New Orleans, Louisiana. Although he had intended to settle in his previously adopted home state of Texas, Hood found that New Orleans offered more opportunities for post-war security, because it had been spared much of the destruction of the war.

He had borrowed $10, 000 from friends in Kentucky, and would begin his new life in New Orleans. New Orleans became home to many ex-Confederate generals. Among them were, James Longstreet, P.G.T. Beauregard, Jubal Early, fellow Kentuckian Simon Buckner, and Fighting Joe Wheeler.

With business associates John C. Barwelli and Fred N. Taylor, Hood established J. B. Hood and Company, Cotton Factors and Commission Merchants, in February 1866. The cotton brokerage initially struggled and at the invitation of Longstreet, Hood took over the operation of his former commander's insurance business.

In 1866, he met and fell in love with Anna Marie Hennen, a native of New Orleans. On April 30, 1868, with Simon Buckner as his best man, John Bell Hood married Anna Marie Hennen. This was his first marriage; he was 35.

To the surprise of many friends, John and Anna Hood began producing children at an alarming

rate – eleven children in ten years, including three sets of twins. Their first daughter Lydia was born in 1869, the next year twins Annabel and Ethel. In 1871 John Bell, Jr. was born, followed by Duncan in 1873. Twins Marion and Lillian were born in 1874, and then another set of twins, Odile and Ida, in 1876. The tenth child, Oswald, was born in 1878, and finally Anna, in 1879. The eight girls and three boys were often referred to as Hood's Brigade.

New Orleans Home of Anna & John Bell Hood

During the period between 1870 and 1879, it appeared Hood prospered in the insurance and cotton businesses and various other enterprises. He also served the community in numerous philanthropic endeavors, as he assisted in fund raising for orphans, widows, and wounded soldiers.

Hood purchased and resided in a spacious house in the upscale Garden District with his wife, their children, and her recently widowed mother. The elegant home still stands at the corner of Camp and Third Street.

During the summer of 1878, a yellow fever epidemic ravaged New Orleans, and resulted in the deaths of more than 3000 people. The annual practice among families who could afford it was to retreat inland to escape the disease. Spending the dangerous months at the Hennen family retreat near Hammond, Louisiana, the Hoods were spared the terror of the epidemic.

But New Orleans was virtually isolated, and the Cotton Exchange had closed. All but two insurance companies in the city went bankrupt. During the winter of 1878 and the spring of 1879, Hood was wiped out financially. He was forced to allow his personal insurance policies to lapse, and he mortgaged his house to its fullest value.

Yellow fever continued to threaten New Orleans during the summer of 1879, but finances would not allow the Hood family to move out of the city. On August 20, a case of yellow fever developed in the house directly across the street from the Hood home. The next day, one month after the birth of their eleventh child, the general's beloved wife Anna was stricken with the fever. After initially appearing to have recovered from the affliction, she became ill after bathing and relapsed.

Anna Marie Hennen Hood died on Sunday, August 24, 1879, at 6:25 pm.

Walter V. Crouch, a close family friend, described the scene in an August 31 letter to Hood's close friend and former subordinate, General Randall Gibson:

I never saw a man so completely crushed in my life... He said that he was completely ruined and now without his wife he had nothing to live for. The precious little lambs who had gone to bed Sunday night knowing nothing of their mother's death, began to come in one by one until nine came in and such a scene I never want to witness again.

After the children left he said, "Major, I have never had the fever, but if I should have it and it's God's will l'm ready to go. I have requested Colonel Flowers to take charge of my children, and to appeal to the Confederate soldiers to support them for I have nothing on earth to leave them.

Completely devastated by the loss of his wife, struggling physically from his crippling war wounds, and under the stress of financial ruin and its impact on the security of his eleven young children, Hood contracted yellow fever on Thursday, August 27.

His eldest daughter, ten-year-old Lydia, fell victim on the same day. At noon on Saturday, August 29th, Lydia died.

Hood was soon advised of his own impending demise. Calmly accepting his fate, he agreed to receive last rites, and a priest at Trinity Episcopal Church, was summoned to his house. Over the next twelve hours, Hood drifted in and out of consciousness.

At 3:30 am Sunday, August 31, 1879, General John Bell Hood shuddered convulsively and died at age 48.

A brief funeral was held the next day, attended only by a few close friends. A salute was fired by a hastily arranged honor guard named the Continental Guards, and Hood's body was laid to rest beside those of his wife and daughter in Lafayette Cemetery Number One, near his Garden District home. A few years later, the remains of General Hood, Anna, and their oldest daughter Lydia were moved to the Hennen family crypt at Metairie Cemetery in New Orleans.

For the next twelve decades, the only information on John Bell Hood's grave was his name, place of birth (misspelled), and his birth and death dates. However, on August 30, 2003, the 124th anniversary of his death, a lavish funeral and memorial service was held by his descendants and Confederate history organizations, and a bronze memorial marker was erected.

Orphans of Anna & John Bell Hood

Famous 1879 picture of the ten Hood orphans.

Within a week, the ten surviving Hood orphans, all under ten years of age, had been left destitute. On his deathbed, Hood had requested that his orphans be taken care of by his old Texas Brigade. As per his request, the Hood Orphan Memorial Publication Fund was set up by former Confederate general, Pierre G. T. Beauregard, for the purpose of raising funds for the children by selling Hood's memoirs. Members of the Texas Brigade sold a family portrait.

With no means of support for the ten surviving orphans Beauregard also organized a campaign to find homes for all the children. They were ultimately adopted by seven different families in Louisiana, New York, Mississippi, Georgia, and Kentucky, and were kept apart at great distances, except for the twins. Eventually, the families came back together.

A charity fund was also established that would ultimately raise over $30, 000 for the support and education of the orphans. Anna would die in infancy and the surviving nine children would receive their shares of the fund at the age of 21.

A braver man, a purer patriot, a more gallant soldier never breathed than General Hood.

-Louise Wigfall Wright

SOURCES

John Bell Hood

General John Bell Hood

John Bell Hood 1831-1879

Wikipedia: John Bell Hood

In Defense of John Bell Hood

Descendants of John Bell Hood

Biography of General John Bell Hood, CSA

General John Bell Hood: Myths and Realities

John Bell Hood &The Army of Northern Virginia

John Bell Hood Historical Society Newsletter – PDF FILE

Source: feedproxy.google.com

Legal Protection of Websites

When learning about how to make a website it is important to make sure to protect ourselves legally. The legal protection of websites is really important whether you are selling physical products, have an affiliate marketing website, an informational website or blog or even just a personal website you make for fun. Benefits of Legal Protection [...]

Source: howtomakea-website.com

Privacy Policy

Privacy Policy for civilwarwomen.blogspot.com

If you require any more information or have any questions about our privacy policy, please feel free to contact us by email at maggiemac6138@yahoo.com.

At civilwarwomen.blogspot.com, the privacy of our visitors is of extreme importance to us. This privacy policy document outlines the types of personal information is received and collected by civilwarwomen.blogspot.com and how it is used.

Log Files

Like many other Web sites, civilwarwomen.blogspot.com makes use of log files. The information inside the log files includes internet protocol ( IP ) addresses, type of browser, Internet Service Provider ( ISP ), date/time stamp, referring/exit pages, and number of clicks to analyze trends, administer the site, track user’s movement around the site, and gather demographic information. IP addresses, and other such information are not linked to any information that is personally identifiable.

Cookies and Web Beacons

civilwarwomen.blogspot.com does use cookies to store information about visitors preferences, record user-specific information on which pages the user access or visit, customize Web page content based on visitors browser type or other information that the visitor sends via their browser.

DoubleClick DART Cookie

.:: Google, as a third party vendor, uses cookies to serve ads on civilwarwomen.blogspot.com.

.:: Google's use of the DART cookie enables it to serve ads to users based on their visit to civilwarwomen.blogspot.com and other sites on the Internet.

.:: Users may opt out of the use of the DART cookie by visiting the Google ad and content network privacy policy at the following URL - http://www.google.com/privacy_ads.html

Some of our advertising partners may use cookies and web beacons on our site. Our advertising partners include ....

Google Adsense

These third-party ad servers or ad networks use technology to the advertisements and links that appear on civilwarwomen.blogspot.com send directly to your browsers. They automatically receive your IP address when this occurs. Other technologies ( such as cookies, JavaScript, or Web Beacons ) may also be used by the third-party ad networks to measure the effectiveness of their advertisements and / or to personalize the advertising content that you see.

civilwarwomen.blogspot.com has no access to or control over these cookies that are used by third-party advertisers.

You should consult the respective privacy policies of these third-party ad servers for more detailed information on their practices as well as for instructions about how to opt-out of certain practices. civilwarwomen.blogspot.com's privacy policy does not apply to, and we cannot control the activities of, such other advertisers or web sites.

If you wish to disable cookies, you may do so through your individual browser options. More detailed information about cookie management with specific web browsers can be found at the browsers' respective websites.

Source: feedproxy.google.com

Mary Theodosia Palmer Banks

Wife of Union General Nathaniel Prentice Banks

On April 11, 1847, Mary Theodosia Palmer of Providence, Rhode Island, married Nathaniel Banks, after a lengthy courtship. They had one son and two daughters together. She served as the first lady of Massachusetts when her husband was the governor (1858-1861).

Nathaniel Prentice Banks was born at Waltham, Massachusetts, on January 30, 1816, the son of a foreman at a Waltham textile mill. Until the age of 14, he attended a one–room school run by his father’s company, and then began working at the mill as a bobbin boy. He also assisted his father in making furniture, and after a few years apprenticed with a mechanic.

Mary Theodosia Palmer Banks

Her dress has three rows of ruffles along the bottom. It has a slight train in the back. Over the dress is a coat with large pagoda sleeves. Along the wrist and sleeve of the coat is lace. A large piece of lace is also decorating the front of the coat. In her hands she holds a closed umbrella. Her hair is split down the middle and pulled back. She is wearing a bonnet on her head.

Banks read widely, attended lectures in Boston given by public figures such as Daniel Webster, participated in a drama club, organized a dancing school, and joined a temperance society. Around the same time, he was also responsible for editing several weekly newspapers and a paper for the factory in which he worked.

While still working at the factory, Banks was also studying law; he was admitted to the bar at 23 years of age, but soon abandoned an unsuccessful law practice in Boston. He also started a debating society, and his energy and his ability to captivate audiences as a public speaker would serve him well later in life.

Political Life

Banks entered politics during the campaign of 1840, speaking locally for the Democratic Party and editing the Lowell Democrat. When the newspaper folded the next year, he established the Middlesex Reporter in Waltham, but that closed in 1842. Another foray into editing also ended with the failure of the publication, the Rumford Journal (1851–1852).

Banks ran unsuccessfully for the Massachusetts House of Representatives in 1844 and 1847, before winning the first of four consecutive one–year terms in 1848 (serving 1849–1852). On federal issues, he supported low tariffs and territorial expansion. While remaining publicly cautious on the slavery question, he developed close ties with Free Soilers, and was elected by a Democratic–Free Soil coalition as Speaker of the Massachusetts House for the 1851 and 1852 sessions.

In 1852, Banks was elected as a Democrat to the U.S. House of Representatives by a slim margin, with Free Soil support but some opposition from his own party. In Congress, he condemned the Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854, which opened those territories to slavery, and broke with the presidential administration of Democrat Franklin Pierce.

Banks joined the American Party (Know Nothings) and was reelected to Congress in 1854 by a coalition of the Know–Nothings, Free Soil Whigs, and other Democrats opposed to the Kansas–Nebraska Act. At the opening of the Thirty-Fourth Congress the anti-Nebraska men gradually united in supporting Banks for speaker, and after one of the bitterest contests in the history of Congress – lasting from December 3, 1855, until February 2, 1856 – he was elected Speaker of the House by three votes on the 133rd ballot. As speaker, he distributed committee positions proportionally among the parties and impressed fellow congressmen with his aptitude for the position.

In 1856, Banks joined the new Republican Party, supporting its unsuccessful presidential nominee, John C. Fremont, and winning reelection to Congress as a Republican. This has been called the first national victory of the Republican party.

Banks resigned his seat in December 1857, and was governor of Massachusetts from 1858 to 1861, a period marked by notable reforms. He supported public education, penal reform, a reduction of the waiting period for naturalized citizens before they could vote – from 14 years to two – and cuts in expenditures during the economic depression that followed the financial panic of 1857. He vetoed a bill allowing black men to serve in the state militia.

In 1860, Banks received a few votes for the Republican vice presidential nomination, which went to Hannibal Hamlin of Maine. In early 1861, he relocated his family to Chicago, where he succeeded George B. McClellan as president of the Illinois Central railway.

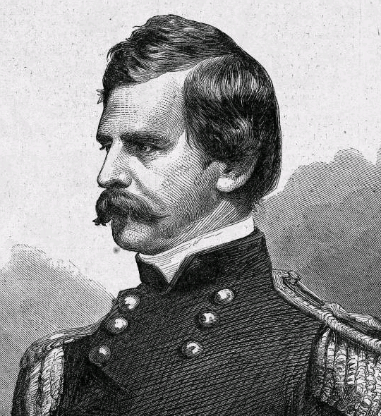

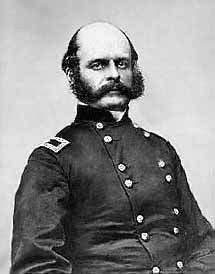

Major General Nathaniel P. Banks, United States Army

Photographed by Matthew Brady

The Civil War

Although as governor he had been a strong advocate of peace, he was one of the earliest to offer his services to President Abraham Lincoln, who appointed him major general of volunteers on May 16, 1861. Banks was one of the most prominent of the volunteer officers. He was first assigned to Annapolis, Maryland, first as division commander and then as department commander, and was an important part of the effort to keep Maryland, a slave state, in the Union.

Unfortunately, Banks had no military experience, but shared the qualities of many political generals. He had courage, but was short on talent; he was a model soldier except in the fields of intuition and training. His heavy mustache and well-groomed appearance complemented his tall, thin frame. It was said that he had the air of one used to being in command.

Shenandoah Valley Campaign

When General George B. McClellan entered upon his Peninsular Campaign (March - July 1862), the important duty of defending Washington DC from the army of Stonewall Jackson fell to the corps commanded by Banks. In the spring, Banks was ordered to move against Thomas Stonewall Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley.

With 38, 000 men, Banks committed himself to driving Jackson from the valley in the hopes of linking up with McClellan and his coming advance on Richmond, the Confederate seat of government. But Jackson, with superior forces, defeated him at Winchester on May 25, and forced him back to the Potomac River. By early June, Jackson had driven Union forces from the Valley. He captured such a large amount of supplies left by the fleeing Union troops that the Confederates nicknamed the Union commander, Commissary Banks.

After that military failure, he was subordinated to Union General John Pope. As commander of the Army of Virginia's 2nd Corps (June – September 1862), Banks was again defeated by Jackson at Cedar Mountain (August 9), where the Union suffered heavy casualties, and Banks didn't perform well at Second Bull Run (Manassas). His decisions at Cedar Mountain were investigated by the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War.

Department of the Gulf

Banks briefly commanded the Military District of Washington, DC (September – October 1862), before President Lincoln selected him to replace General Benjamin Butler as commander of the Department of the Gulf (December 1862 – September 1864). Headquartered in Union–occupied New Orleans, Banks released political prisoners, eased trade restrictions, introduced a system of sharecropping between former slaves and masters, and implemented other changes aimed at appeasing the residents. He also organized several regiments of black Union soldiers, the Corps d'Afrique.

Militarily, Banks continued to perform poorly. Under orders to ascend the Mississippi River and join forces with General Ulysses S. Grant, who was then trying to capture Vicksburg, Banks first pushed a Confederate force up the Teche Bayou and marched to Alexandria, Louisiana, hauling off slaves, cotton, and cattle from a rich agricultural area.

Nathaniel Banks was told that when he united his army with Grant's, he would assume command of both. Banks, then, had the opportunity to become the leading general in the West – perhaps the most important general in the war. But he squandered what successes he had, never rendezvoused with Grant's army, and ultimately orchestrated some of the greatest military blunders of the war.

Because Banks had concentrated on political matters in his first six months as commander of the Department of the Gulf, his attack on Port Hudson was delayed and uncoordinated with the plans of General Grant. Assaults on May 27 and June 14, 1863, resulted in large numbers of Union casualties, but Port Hudson surrendered on July 9, after notification that Vicksburg had fallen to Grant. The entire Mississippi River was then under Union control. Banks received the official Thanks of Congress for Port Hudson, although credit was really due to Grant.

In the autumn of 1863, at the government's direction, Banks organized a number of expeditions to Texas, chiefly for the purpose of preventing the French in Mexico from aiding the Confederates, and to secure stores of cotton, and to restore a Unionist government to the state. He planned a quick thrust at the mouth of the Sabine River, then an overland move upon Houston and Galveston. The invasion resulted in a Union disaster at the Battle of Sabine Pass on September 8, 1863.

Six weeks later, Banks left New Orleans with twenty-three ships and landed an invasion force at Brazos Santiago, near the mouth of the Rio Grande, on November 2, 1863. Union troops soon occupied nearby Brownsville, Texas, and began to drive northward along the coast and up the Rio Grande to shut off the trade coming through the Confederacy's back door. Banks returned to New Orleans just one month after the landing at Brazos Santiago, pressed by his superiors to invade East Texas by way of the Red River.

Major General Nathaniel Prentice Banks

Statue of Nathaniel Prentice Banks at Waltham, Massachusetts

Sculpted by H. H. Kitson; dedicated 1908

Red River Campaign

The Red River Campaign consisted of a series of battles fought along the Red River in Louisiana during the from March 10 to May 22, 1864. The campaign was fought between the 30, 000 Union troops under the command of Major General Banks and Confederate troops under the command of General Richard Taylor (son of former President Zachary Taylor), whose strength varied from 6, 000 to 12, 000.

Banks disagreed with the plan, hoping instead to mount an expedition to capture Galveston, but the movement was ordered by Chief of Staff Henry Halleck. Halleck's plan was approved by President Lincoln, and General Banks went ahead with it under official protest.

Banks' Army was routed at the Battle of Mansfield, and retreated twenty miles to make a stand the next day at the Battle of Pleasant Hill. They continued the retreat to Alexandria, where they rejoined with part of the Federal Inland Fleet. That naval force under David Porter had joined the Red River Campaign intending to take on cotton as lucrative prizes of war, and Banks had allowed rich speculators to come along for the gathering of cotton.

Banks was dependent on Porter's fleet to continue his retreat, but the fleet was trapped above the falls at Alexandria due to dangerously low water levels on the river that supplied the army. Banks approved a plan to build wing dams as a means to raise what little water was left in the channel. In ten days, 10, 000 troops under fire built two dams, and managed to rescue Porter's fleet and Banks' army.

The failure of the campaign effectively ended Banks' military career. When he arrived near the Mississippi, was met by General Edward Canby, who replaced him as the field commander of the Army of the Gulf on the spot.

President Lincoln ordered Banks to return to Washington, DC, to lobby for the president's Reconstruction program. Banks again appeared before the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War to defend his role in the Red River Campaign. The controversy surrounding profits from cotton confiscated during the campaign dogged his later political career. Admiral Porter realized a substantial sum of money during the campaign from the sale of cotton.

The secret presidential investigating commission headed by conservative Democrats William Farrar Smith and James T. Brady in early 1865 devoted considerable effort to trying to connect Banks with vice and irregular trading permits in the New Orleans area. The somewhat one-sided final commission report, which did not specifically accuse him of wrongdoing, was never released.

Following Robert E. Lee's surrender at Appomattox, Banks again served briefly as commander of the Department of the Gulf (April – June 1865) before being mustered out of the U. S. Army on August 24, 1865. Congress later awarded him a $1, 200 annual pension.

In late 1865, Banks was elected as a Republican from Massachusetts to fill a vacant seat in Congress. As chairman of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs (1865–1873), Banks criticized the British for refitting Confederate ships during the Civil War, voted for the purchase of Alaska from Russia, but failed to gain passage of a resolution allowing the president to establish Haiti and Santo Domingo (today, the Dominican Republic) as U.S. protectorates.

In July 1872, upset with President Ulysses S. Grant over administration scandals, Banks announced his support of challenger Horace Greeley, the presidential nominee of the Liberal Republican and Democratic Parties. The endorsement cost Banks his congressional seat that fall, but the next year he was elected as an independent to the Massachusetts Senate, where he supported labor reform and women's suffrage.

In 1874, running as an independent, Banks was returned to Congress, and two years later won reelection as a Republican. He served as U.S. marshal of Boston from 1878 until resigning in 1888, while under investigation for the misuse of funds.

Banks was reelected to Congress in 1888, although he was showing signs of dementia. After failing to win nomination in 1890, he retired from public service. He spent his last years at home with his family, plagued by what is assumed to be Alzheimer's disease.

Nathaniel Prentice Banks died at Waltham, Massachusetts, on September 1, 1894, at the age of 78. He was survived by a son and two daughters.

SOURCES

Nathaniel P. Banks

Red River Campaign

Nathaniel Prentice Banks

Nathaniel Prentiss Banks

Handbook of Texas Online

Governors of Massachusetts

Wikipedia: Nathaniel Prentice Banks

Nathaniel Prentice Banks (1816 – 1894)

King of Louisiana, 1862-1865, and Other Government Work

Source: feedproxy.google.com

How to treat post-burn itching?

Mr. Mashburn, a worker at a paper-recycling plant, fell through a loose grate and into a sump pit in September 2008 as he was preparing to inspect a steam valve. Super hot condensate, at a temperature of at least 140 degrees Fahrenheit, enveloped his legs instantly, searing skin up to his thighs. A co-worker was able to pull Mr. Mashburn out of the pit within 30 seconds, sparing him a worse fate, but he was left with first-, second- and third-degree burns on both legs........

Mr. Mashburn, a worker at a paper-recycling plant, fell through a loose grate and into a sump pit in September 2008 as he was preparing to inspect a steam valve. Super hot condensate, at a temperature of at least 140 degrees Fahrenheit, enveloped his legs instantly, searing skin up to his thighs. A co-worker was able to pull Mr. Mashburn out of the pit within 30 seconds, sparing him a worse fate, but he was left with first-, second- and third-degree burns on both legs........ Source: medicineworld.org

Mary Richmond Bishop Burnside

Wife of Union General Ambrose Burnside

Mary Richmond Bishop was the daughter of Nathaniel and Fanny Windsor Bishop of Bristol, Rhode Island. Her father was a Rhode Island Militia Major. Mary was described as somewhat religious, a rather tall, and a stately young woman, who conveyed a courtly presence.

Ambrose Everett Burnside was born in Liberty, Indiana on May 23, 1824, the son of a South Carolina slaveowner who had freed his slaves and moved his family to Indiana. At the age of 19, Burnside, through his father's political connections was appointed to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. He graduated in 1847, ranked 18 out of 38 in his class, and was commissioned a second lieutenant in the 2nd U.S. Artillery.

He was appointed to an artillery unit in the Mexican-American War. He arrived too late to see any action, but continued to serve with the Artillery in the newly acquired territories in the Southwestern United States. Official Army documents record that Burnside was wounded by an arrow in his neck during a skirmish against Apaches in Las Vegas, New Mexico, but saw no other action under fire.

Mary Bishop Burnside

In 1852, Burnside was appointed to the command of Fort Adams in Newport, Rhode Island. He met Miss Mary Bishop one evening at a Militia Ball held at the Old Armory in Providence, during his first visit to that city. But Burnside was soon ordered to return to the far western frontier to serve again in the Apache Wars, which interrupted their romance, but he soon returned to Rhode Island.

Ambrose Burnside married Mary Richmond Bishop on April 27, 1852. Although Mary dearly loved children and favored two nieces in the Burnside family, Ambrose and Mary had no children of their own.

While serving on the plains, Burnside became dissatisfied with the standard army carbine. In November 1852, Burnside resigned his commission in the US Army, but kept a position in the state militia. He took up permanent residence in Rhode Island, and devoted his time and energy to designing and patenting a breech-loading rifle that bears his name, the Burnside Carbine. The carbine used a special brass cartridge, also invented by Burnside.

With a working model, Burnside established his first company, Burnside & Bishop, which was destroyed by fire in late 1853. With the insurance money, he then formed the Bristol Firearms Company in January 1854 in Bristol, Rhode Island. Mary's family invested heavily in his venture, and Burnside was able to acquire the services of a respected Massachusetts gunsmith, George P. Foster, during the infancy stage of his corporate development.

In August, 1857, a board of army officers reported favorably upon the Burnside breechloader. The Secretary of War under President James Buchanan, John B. Floyd, contracted with the Bristol Firearms Company to equip a large portion of the Army with his carbine, and induced Burnside to establish a factory for its manufacture, which was established as the Bristol Rifle Works.

The works were no sooner complete than another gun maker allegedly bribed Floyd to break his $100, 000 contract with Burnside. At that same time, Burnside ran as a Democrat for one of the Congressional seats in Rhode Island in 1858, and was defeated in a landslide. The burdens of the campaign contributed to his financial ruin. During the Civil War, the Burnside Carbine came into its own. More than 55, 000 rifles were produced for the US Army from 1857 to 1865, and it was the third most used carbine utilized by the Union cavalry.

Burnside was forced into bankruptcy and had to hand over his rights in the company to his creditors. He pledged all of his personal property to the liquidation of his debts, and by practicing strict economy, Burnside eventually paid every obligation. He got a job in Chicago under future Union General George B. McClellan, then vice-president of the Illinois Central Railroad, where Burnside became treasurer. Burnside’s connection with the Illinois Central continued for the rest of his life. After the war he was one of many ex-Generals to be appointed to the boards of railway companies.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Burnside was a Brigadier General in the Rhode Island Militia. He raised a regiment, the First Rhode Island, and was appointed its Colonel on May 2, 1861. Within a month, he ascended to brigade command in the Department of Northeast Virginia. He inexpertly commanded the brigade at the Battle of First Bull Run, and was promoted to Brigadier General in the Union Army.

Burnside began to work on a plan to seize parts of the southern coastline that would involve a force 12, 000 to 15, 000 strong, recruited from coastal areas of New England. This force would descend on lightly defended parts of the coast, seize strategically located places, and gain control of the coastal waters of the Confederacy. McClellan approved of the plan, with Burnside commanding the new North Carolina Expeditionary Corps – three brigades assembled at Annapolis, MD – and the Department of North Carolina from September 1861 until July 1862.

By the start of 1862, Burnside was ready to move. He conducted a successful amphibious campaign that closed over 80% of the North Carolina seacoast to Confederate shipping for the remainder of the war. For his successes at the battles of Roanoke Island, New Bern, Beaufort, and Fort Macon – the first significant Union victories in the Eastern Theater – Burnside was promoted to major general on March 18, 1862.

Major General Ambrose Burnside

Burnside was a tall and handsome man of soldierly bearing, with charming manners, which won for him many friends and admirers.

Following McClellan's failure in the Peninsula Campaign, March through August 1862, Burnside was offered command of the Army of the Potomac. Refusing this opportunity, in part due to his loyalty to McClellan, he detached part of his corps in support of Major General John Pope's Army of Virginia in the Northern Virginia Campaign. Again offered command following the debacle at Second Bull Run, in that campaign, he again declined. Confident in his ability to command smaller armies, Burnside was not so confident that he could carry the burden of commanding the main army of the Union.

Burnside was given command of the Right Wing of the Army of the Potomac (the I and IX Corps) during the Maryland Campaign. He fought at South Mountain and then at the Battle of Antietam in September 1862, where his two corps were placed on opposite ends of the Union battle line. He nonetheless remained in wing command over the IX Corps — a cumbersome arrangement that may explain his slowness in attacking and crossing what is now called Burnside Bridge. The delay allowed Confederate Lt. General A. P. Hill's Confederate division to come up from Harpers Ferry and repulse the Union breakthrough.

McClellan was removed after failing to pursue General Robert E. Lee's retreat from Antietam, and despite his relatively poor performance at Antietam, when Lincoln returned to his search for a new commander for the Army of the Potomac, it was Burnside he turned to. Although he still felt that he wasn't capable of performing the job, Burnside reluctantly accepted the role, possibly because the most likely alternative was General Hooker, whom Burnside considered even less suited for high command. On November 10, 1862, General Ambrose Burnside replaced General McClellan in command of the Army of the Potomac.

President Abraham Lincoln pressured Burnside to take aggressive action and on November 14, 1862, approved his plan to capture the Confederate capital at Richmond, Virginia. Burnside's plan was sound. He would march the Army of the Potomac to Fredericksburg, cross the river on pontoon boats before Lee's widely separated Confederate forces could unite to stop him, and attempt to capture Richmond. When the army reached Fredericksburg on November 17, there were very few Confederates on the opposite bank. There were also no pontoon boats. By the time they arrived, so had the Confederates.

On December 13, 1862, Burnside launched a frontal assault on strong Confederate defenses on the hills above Fredericksburg, and was repulsed with heavy losses. The Battle of Fredericksburg was a humiliating and costly defeat for the Union. His lack of resolution led to his losing the battle, in addition to disappointing Lincoln and injuring the army's morale. Accepting full blame for the loss, Burnside offered to retire from the army, but this was refused.

In January 1863, in an attempt to make up for Fredericksburg, General Burnside decided to cross the Rappahannock River and attack the Confederates from behind. As the troops began moving, it began raining heavily, with strong winds. By the end of the day, the march across the river was a muddy, disorganized mess, which was later called Burnside's Mud March. In its wake, he asked that several officers be relieved of duty and court-martialed, and he also offered to resign. Lincoln accepted his resignation, and on January 26, replaced him with Major General Joseph Hooker.

But President Lincoln was unwilling to lose Burnside completely. Unlike many failed generals, Burnside made it clear that he didn't consider himself suited to command at the highest level. In March 1863, Lincoln sent Burnside to Kentucky as commander of the Department of the Ohio, with orders to move into East Tennessee, where the population was strongly pro-Union. His advance was to be timed to coincide with Union General William Rosecrans' attack on Chattanooga, further to the south. After lengthy delays in front of Chattanooga, General Rosecrans finally made his move in August 1863.

In the Knoxville Campaign, Burnside's expedition progressed well. He captured Knoxville, the main city in East Tennessee, on September 2. One week later he captured the main Confederate army in East Tennessee at Cumberland Gap. Believing that he had achieved what he had been appointed to do, Burnside once again attempted to resign, but his resignation was refused.

After General Rosecrans was defeated at the Battle of Chickamauga, Burnside's command was in serious danger of attack. In the middle of November, that danger was realized when a major expedition under Confederate General James Longstreet was detached from the siege of Chattanooga with orders to recapture Knoxville and East Tennessee. Burnside skillfully outmaneuvered Longstreet and was able to reach his entrenchments and safety in Knoxville, where he was besieged, but Longstreet withdrew, eventually returning to Virginia.

Equestrian Monument to General Ambrose Burnside

Burnside Park, Providence, RI

Burnside was rewarded for his skilful performance at Knoxville with command of the IX Corps. After a period of reorganization in Maryland, that corps joined General Grant for the Overland Campaign. They fought at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House, and Bethesda Church, where Burnside performed in a mediocre manner, appearing reluctant to commit his troops to frontal assaults after his Fredericksburg experience. After Cold Harbor, Burnside took his place in the siege lines at Petersburg, Virginia, in July 1864.

Trench Warfare at Petersburg

At Petersburg, Burnside agreed to a plan suggested by a regiment of Pennsylvania coal miners in his corps: to dig a mine under a fort in the Confederate entrenchments and ignite explosives there to achieve a surprise breakthrough. Only hours before the infantry attack, General George Meade decided it was too dangerous for Burnside to use his division of black troops, who had been specially trained for this mission.

Burnside couldn't decide who to send in their place, so he had his three subordinate commanders draw lots. The division chosen by chance was that commanded by Brigadier General James H. Ledlie – Burnside's worst division. Instead of going around the huge crater created by the blast, Ledlie's men marched into it, became trapped, and were subjected to murderous fire from Confederates around the rim, resulting in high casualties. Ledlie was reported to be drunk, and well behind the lines during the battle.

General George Meade blamed Burnside for the fiasco at the Crater, and Burnside was relieved of command on August 14 and placed on leave. A court of inquiry was convened in August, finally ending on September 9, after seventeen days. The court criticized Burnside for 'failure to comply with orders and to apply military principles, ' but was satisfied that Burnside believed that he had taken the correct actions before the attack. Four other officers were also criticized. Even Grant was (indirectly) criticized, for failure to appoint a single officer to command all troops taking part in the operation.

In December, 1864, Burnside met with President Lincoln and General Ulysses S. Grant about his future. He was contemplating resignation, but Lincoln and Grant requested that he remain in the Army. He was never recalled to duty, and finally resigned his commission on April 15, 1865.

The Burnside House

The distinctively designed Burnside House is made of red-orange brick with a mansard roof. Overall the style of the house is very eclectic and gives an innovative solution to its steep lot. It was finished in 1867 with an estimated total cost of $75, 000, and was referred to as "one of the finest modern houses in Providence." General Burnside inhabited the house until his death in 1881.

After the war, Ambrose Burnside had successful business and political careers, serving as a director of the Illinois Central Railroad, and as president of several other railroad companies, including the Cincinnati & Martinsville Railroad, the Indianapolis & Vincennes Railroad, and the Rhode Locomotive Works.

Burnside was elected to three one-year terms as Governor of Rhode Island from 1866–1868. He was President of the Veterans' Association of the Grand Army of the Republic. The National Rifle Association chose him as their first president at its inception in 1871.

He was also elected to two six-year terms as US Senator from Rhode Island in 1870 and 1876, which post he held until his death. During his tenure, he served as chairman of Senate Education and Labor Committee, and the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

Mary Richmond Bishop Burnside died in 1876.

Major General Ambrose Burnside died very suddenly on September 13, 1881, from neuralgia of the heart at his home in Bristol, R.I. During the funeral ceremonies, he was remembered for his valuable service as a soldier and as a statesman, and in his adopted state, he was the most conspicuous man of his time. He and Mary are buried side by side at Swan Point Cemetery at Providence.

Gravestones of Mary and Ambrose Burnside

Some historians believe that General Burnside has been treated unfairly, not only during his lifetime but throughout written history as well. The traditional view is that he was a poor commander. Those who are inclined to be more charitable toward him ascribe his failures to politics, insubordination, a lack of adequate communication in the field, or at times, just plain bad luck.

Burnside is commonly referred to as Rhode Island's Own in recognition of his years of loyal service to his adopted state. Another of General Burnside's legacies is the term sideburns, which originated from his bushy side-whiskers, joining his ears to his mustache, but with a clean-shaven chin.

SOURCES

Ambrose Burnside

Ambrose Everett Burnside

Ambrose Burnside 1824 – 1881

Wikipedia: Ambrose Burnside

Major General Ambrose E. Burnside

Ambrose Everett Burnside Biography

Ambrose Everett Burnside 1824 – 1881

Major General Ambrose Everett Burnside

Grave of General Ambrose Everett Burnside

Source: feedproxy.google.com

Skin cancer risk from beach vacations

PHILADELPHIA Vacationing at the shore led to a 5 percent increase in nevi (more usually called "moles") among 7-year-old children, as per a paper published in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. Number of nevi is the major risk factor for cancerous melanoma, the most dangerous form of skin cancer. Melanoma rates have been rising dramatically over recent decades. More than 62, 000 Americans are diagnosed with melanoma each year and more than 8, 000 die........

PHILADELPHIA Vacationing at the shore led to a 5 percent increase in nevi (more usually called "moles") among 7-year-old children, as per a paper published in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. Number of nevi is the major risk factor for cancerous melanoma, the most dangerous form of skin cancer. Melanoma rates have been rising dramatically over recent decades. More than 62, 000 Americans are diagnosed with melanoma each year and more than 8, 000 die........ Source: medicineworld.org

Website Analysis Tools - Free

One of the most important tools after learning how to make a website is to have good analytics program. Free website analysis tools for websites is crucial for success and include lots of functions, such as, traffic analysis, and the details of the traffic, like who, what, from where and how much. Free website analysis must [...]

Source: howtomakea-website.com

Post a Comment