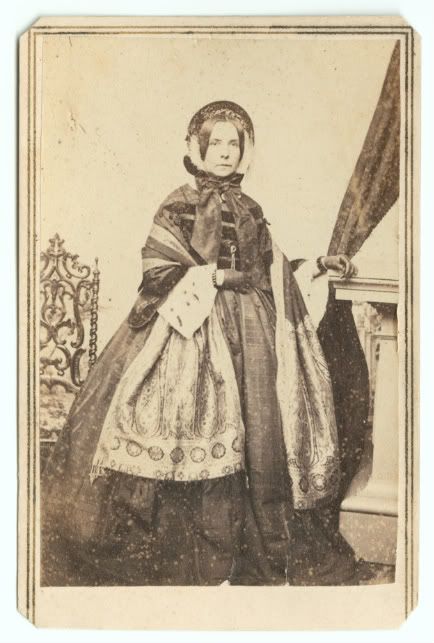

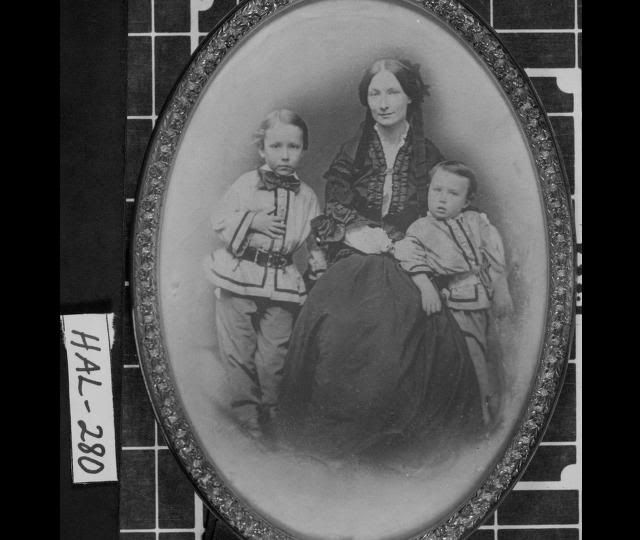

Charlotte Maria Cross Wigfall

Wife of Confederate General and Senator

Charlotte Maria Cross was born in 1818, and there is no further information about her early years. Louis Trezevant Wigfall was born April 21, 1816, on a plantation near Edgefield, South Carolina, to Levi Durant and Eliza Thomson Wigfall, a well-to-do socially-prominent couple. His father, who died in 1818, was a successful Charleston merchant before moving to Edgefield.

His mother was of the French Huguenot Trezavant family, and died when young Louis was 13. He was reared in a privileged and extremely class-conscious society. He immersed himself in the agrarian culture of the region and devoted himself to preserving and expanding it.

Tutored by a guardian until 1834, Louis then spent a year at Rice Creek Springs School, a military academy near Columbia, South Carolina, for children of elite aristocrats. He attended the law department of the University of Virginia at Charlottesville. A perceived insult by another student prompted the first of many dueling challenges he would make.

Charlotte Maria Cross Wigfall

In 1836, he entered South Carolina College to complete his studies, and graduated in 1837. Most of his time was spent at off-campus taverns rather than at his studies. During this time, he abandoned academics altogether for three months to fight in the Seminole War in Florida, achieving the rank of Lieutenant of volunteers.

In 1839, Wigfall was admitted to the bar, and returned to Edgefield and took over his brother's law practice. Having squandered his inheritance, and with a proclivity for drinking and gambling, he accumulated debts. He borrowed from friends to maintain a freewheeling lifestyle, including from his second cousin and future bride, Charlotte Maria Cross of Rhode Island, whom he married in 1841.

Business as an upcountry lawyer didn't suit his temperament and sense of purpose, nor prove to be as profitable as he had hoped. Wigfall believed in a society led by the planter class and based on slavery and the chivalric code. He often neglected his law practice for contentious politics.

In a five-month period in 1840, Wigfall managed to get into a fistfight and two duels, three near-duels, and was charged, but not indicted, for killing a man. This orgy of violence culminated in 1840 on an island in the Savannah River, where he took a bullet through both thighs while dueling with future Congressman Preston Brooks. His reputation as a duelist, often exaggerated, followed him his entire life, though he gave up the practice entirely after his marriage.

His initial foray into politics and the Brooks affair destroyed his law practice. He was elected delegate to the South Carolina Democratic Convention in 1844, but his violent temperament and behind-the-scenes meddling had already doomed his youthful political ambitions. He piled up medical bills on a sickly infant son who eventually died. Sheriff sales followed, swallowing up his Edgefield estate.

Wigfall witnessed South Carolina's dispute with the federal government over tariffs and became a lifelong advocate of states' rights. He carried his two core beliefs - in the romance of the Old South and the sovereignty of individual states - with him to Texas in 1848.

After Texas joined the United States in 1846, tens of thousands of immigrants poured across its borders in search of cheap land and new lives. Most came from the American South, which by then had developed a distinct culture based upon cotton and slavery.

A Texas cousin, James Hamilton, Jr., a former governor of South Carolina, arranged a fresh start for Wigfall, and a law partnership. First arriving in Galveston in 1848, he then moved with his wife, Charlotte, and their three children to Nacogdoches, where he was a law partner of Thomas J. Jennings and William B. Ochiltree. Soon Wigfall opened his own law office in Marshall.

Wigfall was active in Texas politics from the moment he arrived, alerting Texans to the dangers of abolition and the growing influence of non-slave states in the United States Congress. He quickly established himself as one of the community's most ardent and vocal fire-eaters, a name given to Southerners who supported radical means to defend slavery and states' rights.

At the Galveston County Democratic convention in 1848, Wigfall condemned congressional efforts to prohibit the expansion of slavery into the territories, and expressed sorrow that Texas would not take the lead in opposing such unconstitutional actions.

Wigfall served in the Texas House of Representatives from 1849–1850, and in the Texas Senate from 1857–1860. He played a major role in organizing Texas Democrats and fighting the American (Know-Nothing) party in 1855-56.

When Senator Sam Houston ran for governor in 1857, Wigfall followed him on the campaign trail, attacking his congressional record at each of Houston's stops, and accusing Houston of being a coward and a traitor to Texas and the South. Wigfall claimed that Houston had ambitions for a presidential nomination and courted the support of Northern abolitionists. Wigfall was one of the few men in Houston's opposition who rivaled him as a stump speaker, and he was widely credited with Houston's defeat for the governorship in 1857.

In 1858, Wigfall had a strong voice in the state Democratic convention that adopted a states' rights platform. With the breakup of the Know Nothing Party, many moderates moved back into the Democratic party, and it appeared that Wigfall's radicalism was repudiated. But he capitalized on the fear that John Brown's raid on Harper's Ferry caused in the slave states.

In 1859, Wigfall was selected by the legislature to represent Texas in the United States Senate, filling the vacancy caused by the death of J. Pinckney Henderson and served from December 5, 1859, until March 23, 1861. As "the most violent partisan in the state, " according to one contemporary, Wigfall was a natural choice for a state that was more and more supportive of the political position of the Deep South.

In the Senate, he became a leader in the effort to assure southern slave-owner's freedom to settle in the territories with their slaves. He continued his by-now familiar diatribes against federal powers and northern intrusion into southern life. He rarely concerned himself with Texas, but identified closely with his native South Carolina.

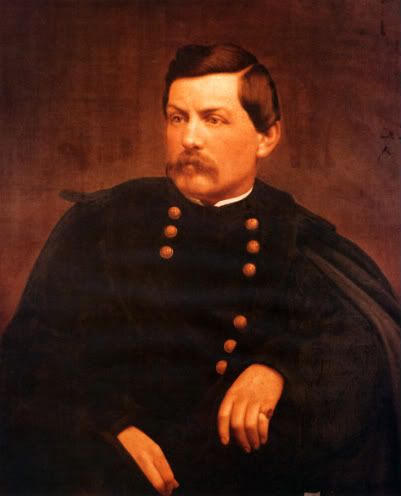

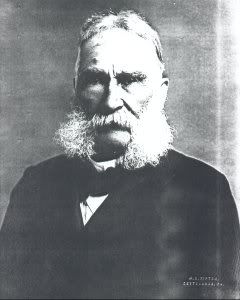

Louis Trezevant Wigfall

Wigfall was among a group of leading secessionists known as Fire Eaters. He earned a reputation for eloquence, acerbic debate, and readiness for encounter. He continued his fight for slavery and states' rights and against expanding the power of national government. His reputation for oratory and hard-drinking, along with a combative nature and high-minded sense of personal honor, made him one of the more imposing political figures of his time.

One of the most vociferous advocates for secession, and one of the people most responsible for tying the fortunes of the Lone Star State to the Confederacy, was Louis T. Wigfall. Texas had become a part of the Old South, and when southern states began leaving the Union in 1860, Texas followed suit. In 1860, Wigfall was instrumental in fracturing the Democratic Party, hoping to kill any possibility of compromise between north and south.

Insisting that the Democratic party platform of 1860 call for the Federal government to guarantee protection of slavery in the territories, he was key to the split of the Democratic party and the subsequent election of Abraham Lincoln as president.

Wigfall coauthored the Southern Manifesto, declaring that any hope for relief in the Union was gone, and that the honor and independence of the South required the organization of a Southern Confederacy. Wigfall helped foil efforts for compromise to save the Union and urged all slave states to secede. When South Carolina led the parade of southern states out of the Union, Wigfall rejoiced.

Wigfall joined the Texas delegation to the Montgomery Conference in Alabama, which formed the provisional government of the Confederacy, and which selected Jefferson Davis as its president. In Washington, Wigfall continued to hold his seat for 6 days after Texas had seceded on March 1, 1861, exhorting the rightness of the Southern cause and berating his Northern colleagues on the floor of the Senate and in Capitol Hill saloons.

During this time in Washington, he spied on Federal preparations for the coming conflict, secured weapons for delivery south, and went to Baltimore, Maryland, and recruited soldiers for the new Confederacy before traveling to the Confederate capital at Richmond, Virginia. He was one of ten Southern senators who were expelled in absentia on July 11, 1861.

He was admitted to the Provisional Confederate Congress on April 29, 1861, where he served on the Committee on Foreign Affairs. Wigfall was at Fort Sumter in April 1861 when the Civil War began, gleefully demanding the surrender of the Federal post. Between April and July 1861, he was a member of the Provisional Congress of the Confederacy, and served as an aide to Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

Wigfall continued his service to the Confederacy as a military commander - without great distinction, as according to many accounts he was often inebriated. He was commissioned colonel of the First Texas Infantry on August 28, 1861, and on November 21 Davis nominated him brigadier general in the Provisional Army, a move later confirmed by the Confederate Congress.

Mrs. Wigfall's Wedding Dress

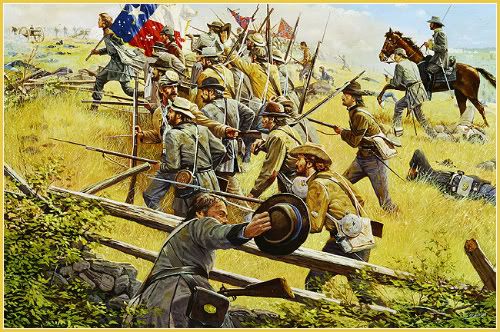

Charlotte Maria Cross Wigfall, wife of the 1st Texas Regiment's Colonel, made her wedding dress into a Lone Star Flag for the Regiment, and presented this flag that she had sewn by hand to the regiment in the summer of 1861. Carried by the 1st Texas Infantry of General John Bell Hood's Brigade, the flag was captured during the Battle of Sharpsburg – September 17, 1862 – after nine of the men who carried it had fallen.

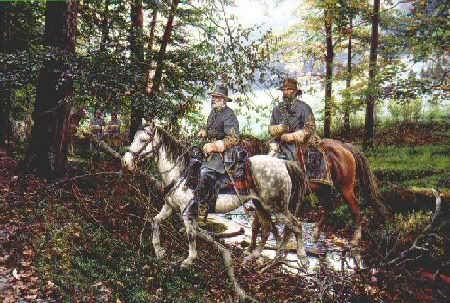

Artist: Dale Gallon

Wigfall commanded the Texas Brigade of the Army of Northern Virginia (Hood's Texas Brigade) until February 20, 1862, when he resigned to take a seat in the Confederate Senate and represented the State of Texas for the remainder of the war. Despite his public advocacy of states' rights, Wigfall did little for Texas. In the Senate, he worked for military strength at the expense of state and individual rights.

An arrogant man, Wigfall came into conflict with President Davis. After the chief executive vetoed Wigfall's bill to upgrade staff positions in the army and limit presidential selection, Wigfall carried his fight into social circles, even going so far as to refuse to stand when Davis entered the room. Although a friend and supporter of the Confederate military, he was also an obstructionist in opposing Davis' nominations.

When Richmond fell, Wigfall fled Virginia. He first went home to Texas for almost a year. In the spring of 1866, he moved to England, and spent six years in self-imposed exile. He practiced law in England, but returned to the United States in 1872, first residing in Baltimore, MD.

Louis Trezevant Wigfall returned to Texas, landing at Galveston in January 1874. He intended to revive his long-dormant law practice, but he died unexpectedly on February 18, 1874, and was buried at Trinity Episcopal Church Cemetery in Galveston. I found no record of the death of Charlotte Maria Cross Wigfall.

SOURCES

Louis Wigfall

The Fire Eaters

Louis T. Wigfall

Louis Trezevant Wigfall

The Handbook of Texas Online

Confederate Gazette – PDF FILE

Ordinance of Secession of Texas

Politicians in Trouble or Disgrace: Texas

Source: feedproxy.google.com

Rebecca (Fanny) Haralson Gordon

Wife of Confederate General John Brown Gordon

Rebecca (Fanny) Haralson, September 18, 1837, and lived almost into our own time, was the daughter of General Hugh Anderson Haralson of LaGrange, Georgia. Her father had represented Georgia in Congress for many years and was Chairman of the Committee on Military Affairs during the Mexican War.

John Brown Gordon was born in Upson County, Georgia, February 6, 1832, to Zachariah and Malinda Cox Gordon, the fourth of twelve children. His father was a prominent Baptist minister and plantation owner. Around 1840, Zachariah moved his family to Walker County near Lafayette, where he built a summer resort hotel to take advantage of the medicinal appeal of the springs on the property. The hotel subsequently became one of the State's most fashionable vacation spots. Over two decades later, the Battle of Chickamauga was waged in part on the Gordon's property.

Fanny met John Brown Gordon after he left the University of Georgia in 1854 to study law in Atlanta. He was admitted to the Bar later that year, and began a law practice with Basil H. Overby and Logan E. Bleckly. Through them, Gordon met Fanny Haralson, who was the younger sister of the wives of both partners.

Fanny Haralson Gordon

In love at first sight, 22-year-old John married Fanny on her 17th birthday, September 18, 1854. The wedding took place at Myrtle Hill, the Haralson's ancestral home near La Grange, Georgia. It was a small private affair in her father's bedroom, because his health had taken a bad turn. In fact, one week later her father, General Haralson, died. Shortly after the wedding, John and Fanny moved to Atlanta. Theirs was a long and happy marriage.

When his practice began to falter, Gordon switched to journalism and wrote for a newspaper in Milledgeville – then Georgia's capital – for a year before moving to northwest Georgia to open a coal mining company. It was there, at the juncture of Georgia, Alabama and Tennessee, that Gordon was living when the Civil War erupted in 1861.

By the time war came, the Gordons had two small boys and were operating a coal mining company. Hus¬band and wife struggled with their loyalties to family and country. Gordon wrote in his memoir that Fanny "ended doubt as to what disposition was to be made of her by announcing that she intended to accompany me to the war. She left their children with relatives to free her up for what in her judgment was a higher duty. Because of Southern custom, she couldn't be a battlefield nurse, but she could stay in the camps while the battles in which John fought were raging nearby.

John Brown Gordon was just 28 years old when the war began, yet by the end of the war, he was second in command only to General Robert E. Lee. In 1861, he enlisted as a private soldier, and was elected captain of a volunteer company he recruited, which was composed of men from the mountains, and they became known as the "Raccoon Roughs."

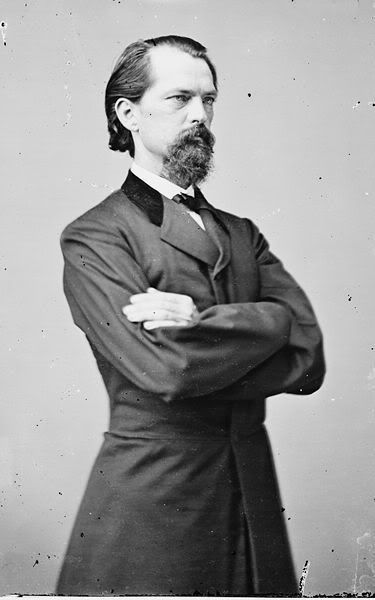

General John Brown Gordon

By Matthew Brady

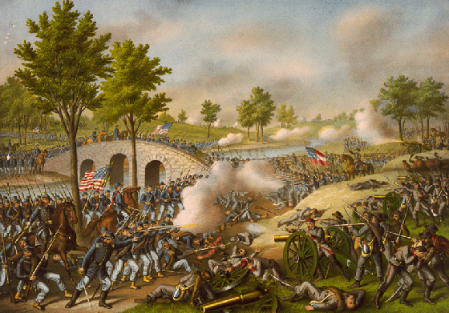

Fanny Gordon accompanied her general throughout the war, and is credited with saving his life when he was wounded five times at Antietam. Assigned by General Lee to hold an essential position during the Battle of Sharpsburg, Gordon's men were tremendously outnumbered. Their only hope, he decided, was for his men to hold their fire until the enemy troops were practically on top of them and then all fire at once. Their first volley knocked down almost the entire Yankee front line. Subsequent lines of Yankees met a similar fate.

But many Confederates also fell at what would be called the Battle of Bloody Lane (a sunken road), including Gordon. First, a minie ball passed through his calf, a second ball hit him higher in the same leg, a third through his left arm, mangling the muscles and tendons in his arm were mangled and severing a small artery. A forth ball hit him in his shoulder. Despite pleas he go to the rear, Gordon continued to lead his men.

General Gordon was finally stopped by a ball that hit him in the face, passing through his left cheek and out his jaw, leaving him helpless and insensible on the field. He fell with his face in his cap and might have drowned in his own blood if there hadn't been a bullet hole in the cap.

Gordon was carried on a litter to a barn where 6th Alabama Assistant Surgeon Thaddeus J. Weatherly dressed his wounds. When Gordon revived late that night he found himself lying on a pile of straw. His spirited young wife Fanny came to the barn as soon as she learned her husband had been wounded. When she reached him, she suppressed a scream as Gordon struggled to joke with her, saying he had been to an Irish wedding.

Fanny nursed her husband for seven months. She dressed his wounds, fed him brandy and beef tea because his jaw was wired shut, and provided long hours of bedside care and devotion. "Thenceforward, for the period in which my life hung in the balance, " the general wrote, "she sat at my bedside, trying to supply concentrated nourishment to sustain me against the constant drainage."

The facial wound caused his face to blacken and swell and his eyes to narrow, so much so that he could barely see. None of this deterred her. His jaw had been wired shut, which made feeding an extremely difficult proposition, but she knelt at his side and managed to get a little liquid nourishment past his clenched teeth.

When erysipelas, a serious bacterial infection, attacked his left arm, she painted it relentlessly with iodine. "Under God's providence, I owe my life to her incessant watchfulness night and day, and to her tender nursing through weary weeks and anxious months, " Gordon recalled. With Fanny's care and his own strong will, Gordon miraculously recovered.

Gordon returned to duty in March 1863 and was given command of a brigade of six Georgia regiments in Lt. General Jubal Early's Division. After leading a successful assault on Marye's Heights in Fredericksburg during the Battle of Chancellorsville in May, Gordon was promoted to brigadier general.

After General Robert E. Lee restructured his army, Early's Division was absorbed into Lt. General Richard Ewell's Second Corps and marched into the Shenandoah Valley as part of Lee's second attempt to invade the North. At Gettysburg on July 1, 1863, Gordon's brigade of 1200 Georgians rolled up the Federal right flank north of the town and was driving the Yankees until ordered to halt by Early and Ewell, which Gordon later contended was a mistake that cost the Rebels the battle.

Gordon was a brilliant and captivating orator – a skill he put to effective use during the War to inspire his men. A Confederate officer at Gettysburg recalled that the sight of Gordon mounted on his magnificent, coal-black stallion as being "the most glorious and inspiring thing" he had ever seen. It was, he declared, an unforgettable "splendid picture of gallantry." Gordon "standing in his stirrups, bare headed, hat in hand, arms extended and, in a voice like a trumpet, exhorting his men" was "absolutely thrilling."

Fanny mostly kept pace, going to the rear before battles. Her husband marveled at her courage. "It requires the direst dangers, especially where those dangers threaten some cause or object around which their affections are entwined, to call out the marvelous courage of women, " Gordon wrote. "Under such conditions they will brave death itself without a quiver."

In the Overland Campaign, Gordon commanded a division in Ewell's (later Early's) corps at the Battle of the Wilderness near the grounds of the Chancellorsville battlefield. His God-given ability to inspire his troops almost to madness was notably done on May 12, 1864, at the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House.

General Lee was prepared to lead the charge of Gordon's men when Gordon rode up and said: "General Lee, this is no place for you. These men behind you are Georgians and Virginians. They have never failed you and will not fail you here." Then they took up the chant, "Lee to the rear, " and Gordon seized Lee's horse's bridle and ordered some men to take Lee to the rear.

Gordon's success in turning back the massive Union assault at the Bloody Angle prevented a Confederate rout, and his erect posture saved his life, as a ball went through the back of his coat, just missing his spine. Some believe that Gordon's success in turning back the Federals at the Bloody Angle gave the Confederacy an additional year of life.

After Cold Harbor, Gordon left with General Jubal Early for the Valley Campaigns of 1864. Unbeknownst to John, Fanny followed him on June 14, 1864. At one point, her carriage broke down and she was almost captured, but with the help of men from the command of Robert Rodes, she continued unmolested.

On September 19, 1864, Fanny rushed out into the street during the Third Battle of Winchester to urge Gordon's retreating troops to go back and face the enemy. With bullets flying all around her, she shouted, "Go back to the front lines, you cowards! Turn around and fight." Fortunately, no harm came to either of them.

Gordon was horrified to find her in the street with shells and balls flying about her. "I saw Mrs. Gordon on the streets of Winchester, under fire, her soul aflame with patriotic ardor, appealing to retreating Confederates to halt and form a new line to resist the Union advance. She was so transported by her patriotic passion that she took no notice of the whizzing shot and shell, and seemed wholly unconscious of her great peril."

Lt. General Jubal Early, a bachelor, had little patience with wives who tried to follow their officer husbands to war. He remarked that he wished the Yankees would capture Mrs. Gordon because she always seemed to be around. Yet when she teased him about the remark during a dinner, Early relented, saying, "Mrs. Gordon, General Gordon is a better soldier when you are close by him than when you are away, and so hereafter, when I issue orders that officers’ wives must go to the rear, you may know that you are excepted."

In December 1864, Gordon was ordered to rejoin the Army of Northern Virginia as commander of the bulk of the Second Corps while Early remained in the Valley. Lee's army faced a siege at Petersburg, Virginia, by Lt. General Ulysses S. Grant and the Army of the Potomac.

Fanny Gordon stayed as near to the general as possible until late in the war – when she was incapacitated by childbirth, and ended up behind enemy lines in Virginia.

General Gordon's career was perhaps as brilliant as that of any officer in the Confederate army. In rapid succession he filled every grade – that of Major, Lieutenant Colonel, Colonel, Brigadier General, Major General, and, near the end, was assigned to duty as Lieutenant General (by authority of the Secretary of War).

For General John Brown Gordon, April 9, 1865, began with leading his weakened and hungry forces into battle at Appomattox Court House, Virginia. When Lee's army had "been fought to a frazzle" and was surrounded by the enemy, General Gordon led the last charge of the Army of Northern Virginia, and captured the entrenchments and several pieces of artillery in his front.

Hours later, the Civil War was over. Gordon commanded, at the surrender at Appomattox, one half of the Army of Northern Virginia, under Robert E. Lee. On April 12, 1865, Gordon's Confederate troops officially surrendered to Major General Joshua L. Chamberlain, who was acting for General Ulysses S. Grant.

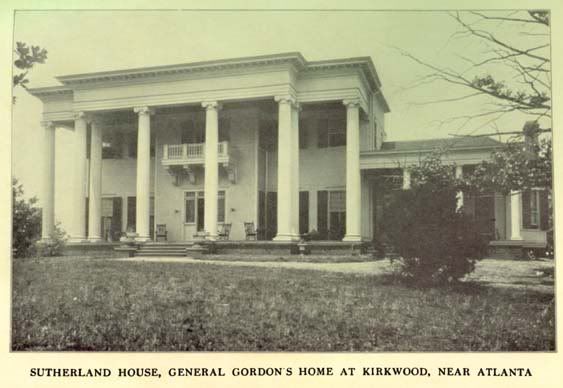

After the war ended, because fighting in North Georgia had damaged the Gordon's coal mines, and they lacked the money needed to reopen them, General Gordon had to look for a new occupation. After briefly owning and managing some sawmills near Brunswick, he moved to Kirkwood, an Atlanta suburb, and went into the insurance and publishing businesses.

Gordon rose through the ranks in civilian life as he had during the war. It must be said that after the war, he was a strong opponent of Reconstruction, and was generally acknowledged to be the titular leader of the Ku Klux Klan in Georgia during the late 1860s – another Southern military figure, fighting to preserve a way of life that had already been lost.

Gordon lost his first run for governor in 1868, but the state Legislature selected him to represent Georgia in the US Senate, where he served from 1873 to 1880. In the Senate, he concentrated on economic issues and fostering national reconciliation. He was hailed by the New York Times as "the ablest man from the South in either House of Congress."

Gordon's career was tainted by scandal in 1880 when, having been reelected to the US Senate, he suddenly resigned to become general counsel of the state-controlled Western and Atlantic Railroad. When Governor Alfred Colquitt promptly appointed the railroad's former president Joseph E. Brown to fill Gordon's unexpired term as senator, a cry went up within his own Democratic Party that a corrupt bargain had been struck.

Although Gordon claimed that he was acting in the best interest of the party and his constituency by retiring from public life, he was never able to fully counter the charges by his critics that he was motivated strictly by personal gain.

None of this, however, detracted from his popularity. In 1886, he was elected governor of Georgia, and he stayed in the position until 1890, then rejoined the US Senate for another six years. When the United Confederate Veterans was organized in 1889, he was made the group's president.

As aggressive and optimistic in business as he had been in war, Gordon invested in a wide variety of businesses and a white elephant plantation in Taylor County. He lost most of his money in a failed venture to build a railroad from Georgia to Key West and establish a steamship line to linking it to Latin America.

Mistakes made by the Memphis branch of the insurance company, whose Atlanta branch Gordon headed, caused the company to go bankrupt. Gordon's financial status remained precarious for the rest of life and gave substance to claims that he exchanged political favors for money.

During the last decade of his life, " says Ralph Lowell Eckert (author of John Brown Gordon: Soldier, Southerner, American) "Gordon remained extremely active in his efforts to vindicate the South and at the same time to establish a new spirit of nationalism" by embarking on a career as a lecturer. He retired from politics in 1896. For several years he lectured, and he published his highly successful memoir, Reminiscences of the Civil War, in 1903.

With Fanny at his side, John Brown Gordon died in Miami at age 71 on January 9, 1904, three months after his memoir, Reminiscences of the Civil War, was published. Despite his extremely debilitated state, he managed a last look, a smile and a touch for the one who had loved him and been loved by him almost from the day their eyes met, who had been with him in body and in spirit for half a century and who had been all things to him.

The general even received a tribute from President Theodore Roosevelt, who summed up what many felt by saying, "A more gallant, generous, and fearless gentleman and soldier has not been seen by our country."

Fanny soldiered on without him for another 27 years, but her life was a pale copy of the life she knew with the knight known as John Brown Gordon, who, it was said, was the only Civil War commander who was never defeated or repulsed when he led a charge or when he was in command.

Rebecca (Fanny) Haralson Gordon died April 28, 1931, at the age of 93 – an almost unheard of longevity in those days.

SOURCES

John Brown Gordon

Shot by Cupid’s Bow

John B. Gordon (1832-1904)

General John Brown Gordon

John and Fanny - A Love Story

Wikipedia: John Brown Gordon

The 9 Lives of General John Brown Gordon

Source: feedproxy.google.com

Ellen Mary Marcy McClellan

Wife of Union General George B. McClellan

Ellen Mary Marcy was born in 1836 in Philadelphia. She was the blonde, blue-eyed daughter of Major Randolph Marcy – explorer of the famous Red River and Federal chief-of-staff in the first years of the war – an army officer who gained a good deal of fame in the decade just before the Civil War, as an explorer of the unsettled West. He was a strictly-business regular who blazed trails across the prairies and paved the way for the opening of the plains country.

Ellen Mary Marcy McClellan

George Brinton McClellan, the son of a surgeon, was born in Philadelphia December 3, 1826. He attended the University of Pennsylvania in 1840 at age 13, resigning himself to the study of law. After two years, he changed his goal to military service. With the assistance of his father's letter to President John Tyler, young George was accepted at the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1842. The academy had waived its normal minimum age of 16, and George graduated second in the class in 1846.

McClellan was appointed to the staff of General Winfield Scott during the Mexican War (1846-48), and won three brevets for gallant conduct. He taught military engineering at West Point (1848-51), and in 1855 was sent to observe the Crimean War in order to obtain the latest information on European warfare.

Due to his intimate knowledge of Texas and Indian Territory geography, Major Randolph Marcy was selected for the Red River Expedition of 1852. Along with several troops and a young army lieutenant he liked very much – George B. McClellan – Marcy set out to discover the source of the Red River. Unlike his predecessors, he didn't use a boat, but explored mainly on horseback. He kept a meticulous diary, made friends with the Indians, and wrote a dictionary of the Wichita language.

In 1854 when McClellan was 27 years old, he met 18-year-old Ellen Mary Marcy, the daughter of his former commander, and it was love at first sight for him. He wrote to Ellen's mother: "I have not seen a very great deal of the little lady mentioned above, still that little has been sufficient to make me determined to win her if I can." Her father did everything he could to persuade the girl to accept him. He had no luck; Ellen simply didn't love McClellan.

She loved Lieutenant Ambrose Powell Hill (future general in the Army of Northern Virginia). She wrote to her father, telling him that she was going to marry Hill, and Marcy promptly blew his stack. Any woman, he told his daughter, who married an army officer was simply asking for trouble; pay was low, absences from home were frequent and extended, and military life offered no particular future. McClellan was also a soldier, but he was planning to leave the army and enter private industry, and his family had money.

Ellen was to abandon all communication with Lieutenant Hill, and "if you do not comply with my wishes in this respect, " her father wrote, "I cannot tell what my feelings toward you will become. I fear that my ardent affections will turn to hate..." Ellen was stubborn, but she listened to her father, and let the matter rest for nearly a year. In the end, Marcy had his way, and Lieutenant Hill at last faded out of the picture. General Ambrose Powell Hill was killed in battle one week before the Confederate surrender at Appomattox.

In June, McClellan proposed and Ellen promptly rejected him. It probably didn't help that she was two or three inches taller than McClellan. Leaving Washington, McClellan continued to keep in touch with Ellen and the family. Life for Ellen was going quickly as George continued his quest by mail. Before she reached the age of 25, she had received and rejected nine proposals of marriage.

McClellan left the United States Army in 1857 to become chief of engineering and vice president of the Illinois Central Railroad, where he became acquainted with Abraham Lincoln, the company's attorney. He became president of the Ohio and Mississippi Railroad in 1860. He performed well in both jobs, but despite his successes and lucrative salary ($10, 000 per year), he was frustrated with civilian employment and continued to study classical military strategy.

In 1859, Major Marcy was ordered west, and the family visited McClellan in Chicago. On October 20, George again proposed marriage, and this time Ellen accepted. Ellen and George were married at Calvary Church, New York City, on May 22, 1860. McClellan was 33 and Ellen was 25.

They had a son and a daughter: George Brinton McClellan, Jr. who was born in Dresden, Germany, during the family's first trip to Europe. Known to the family as Max, he served as a US Representative from New York State and as Mayor of New York City from 1904 to 1909. Their daughter, Mary ("May"), married a French diplomat and spent much of her life abroad. Neither Max nor May gave the McClellans any grandchildren.

The two would remain married for 25 years and were devoted to each other, writing daily when separated. "My whole existence is wrapped up in you, " he wrote in one such letter. McClellan's personal life was without blemish. If Ellen Marcy ever regretted the turn of events, she left no record of it, coming down in history as a pretty, rather sad young woman looking out of the Brady photographs.

According to legend, Hill nourished a grudge against McClellan, and fought against him during the Civil War with more than ordinary vigor. Whenever the Confederates attacked the Army of the Potomac (which happened fairly often during the summer of 1862), the Union soldiers ascribed it to A. P. Hill and his personal feud with McClellan.

The story was told that McClellan was aroused from sleep early one morning by the crackling musketry from the picket line where Hill's division was opening another assault. McClellan detached himself grumpily from his blankets, and screamed these words: "My God, Ellen! Why didn't you marry him?"

McClellan offered his services to President Abraham Lincoln on the outbreak of the American Civil War. On May 3, 1861, he was named commander of the Department of the Ohio, responsible for the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and, later, western Pennsylvania, western Virginia, and Missouri. On May 14, he was commissioned a major general in the regular army, and at age 34 outranked everyone in the Army except Lt. General Winfield Scott, the general in chief.

General George Brinton McClellan

By Alexander Lawrie

Date unknown

On July 26, 1861, the day he reached the capital, McClellan was appointed commander of the Military Division of the Potomac, the main Union force responsible for the defense of Washington. On August 20, several military units in Virginia were consolidated into his department, and he immediately formed the Army of the Potomac, with himself as its first commander. He reveled in his newly acquired power and fame.

He grasped the magnitude of his new assignment, telling Ellen:

I find myself in a new and strange position here — President, Cabinet, General Scott & all deferring to me — by some strange operation of magic, I seem to have become the power of the land... I almost think that were I to win some small success now, I could become Dictator or anything else that might please me — but nothing of that kind would please me — therefore I won't be Dictator. Admirable self-denial!

–George B. McClellan, letter to Ellen, July 26, 1861

During the summer and fall, McClellan brought a high degree of organization to his new army, and greatly improved its morale by his frequent trips to review and encourage his units. It was a remarkable achievement, in which he came to personify the Army of the Potomac and reaped the adulation of his men.

He created defenses for Washington that were almost impregnable, consisting of 48 forts and strong points, with 480 guns manned by 7, 200 artillerists. But this was also a time of tension in the high command, as he continued to quarrel frequently with the government and the general-in-chief, Lt. General Winfield Scott, on matters of strategy.

McClellan's antipathy to emancipation added to the pressure on him, as he received bitter criticism from Radical Republicans in the government. He viewed slavery as an institution recognized in the Constitution, and entitled to federal protection wherever it existed.

The dispute with Scott would become very personal. Scott (along with many in the War Department) was outraged that McClellan refused to divulge any details about his strategic planning, or even mundane details such as troop strengths and dispositions. McClellan claimed not to trust anyone in the administration to keep his plans secret from the press, and thus the enemy.

On November 1, 1861, General Winfield Scott retired, and McClellan became general in chief of all the Union armies. The president expressed his concern about the "vast labor" involved in the dual role of army commander and general-in-chief, but McClellan responded, "I can do it all." But Lincoln, as well as many other leaders and citizens of the northern states, became increasingly impatient with McClellan's slowness to attack the Confederate forces still massed near Washington.

McClellan further damaged his reputation by his insulting insubordination to his commander-in-chief. He privately referred to Lincoln, whom he had known before the war, as "nothing more than a well-meaning baboon", a "gorilla", and "ever unworthy of... his high position." On November 13, the president visited McClellan at his house, he made him wait for 30 minutes, only to be told that the general had gone to bed and could not see him.

McClellan insisted that his army should not undertake any new offensives until his new troops were fully trained. He developed a strategy to defeat the Confederate Army by invading Virginia from the sea, and to seize Richmond, and then other major cities in the South. McClellan believed that to keep resistance to a minimum, it should be made clear that the Union forces would not interfere with slavery and would help put down any slave insurrections.

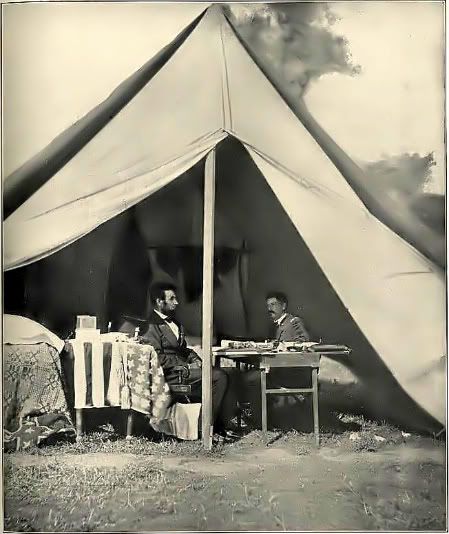

Ellen Mary Marcy and Major General George B. McClellan

McClellan appointed Allan Pinkerton to employ his agents to spy on the Confederate Army. His reports exaggerated the size of the enemy, and McClellan was unwilling to launch an attack until he had more soldiers available. Under pressure from Radical Republicans in Congress, Abraham Lincoln decided in January, 1862, to appoint Edwin M. Stanton as his new Secretary of War.

Soon after this appointment, President Abraham Lincoln ordered McClellan to appear before a committee investigating the way the war was being fought. On January 15, 1862, he had to face the hostile questioning of Benjamin Wade and Zachariah Chandler. Wade asked McClellan why he was refusing to attack the Confederate Army. He replied that he had to prepare the proper routes of retreat.

Chandler then said: "General McClellan, if I understand you correctly, before you strike at the rebels you want to be sure of plenty of room, so that you can run in case they strike back." Wade added, "Or in case you get scared." After McClellan left the room, Wade and Chandler came to the conclusion that McClellan was guilty of "infernal, unmitigated cowardice."

As a result of this meeting, Abraham Lincoln decided he must find a way to force McClellan to attack. On January 31, he issued General War Order Number One, which ordered McClellan to begin the offensive against the enemy before February 22. Lincoln also insisted on being consulted about McClellan's military plans.

On March 11, 1862, Lincoln removed McClellan as general in chief, leaving him in command of only the Army of the Potomac, so that McClellan could devote all his attention to the capture Richmond, the Confederate capital. Lincoln's order was ambiguous as to whether McClellan might be restored following a successful campaign.

Lincoln, Stanton, and a group of officers, called the War Board, directed the strategic actions of the Union armies that spring. Although McClellan was assuaged by supportive comments from Lincoln, in time he saw the change of command very differently, describing it as a part of an intrigue "to secure the failure of the approaching campaign."

The Peninsula Campaign

McClellan and the Army of the Potomac took part in what became known as the Peninsula Campaign, a major Union operation launched in southeastern Virginia from March through July 1862, the first large-scale offensive in the Eastern Theater. Lincoln disagreed with McClellan's desire to attack Richmond from the east, and only gave in when the division commanders voted eight to four in favor of McClellan's strategy. The main objective was to capture Richmond, the Confederate capital.

In March 1862, McClellan moved his troops into the Shenandoah Valley, and along with John C. Fremont, Irvin McDowell, and Nathaniel Banks surrounded Thomas Stonewall Jackson and his 17, 000 man army. Jackson won victories in the valley at McDowell, Front Royal, Winchester, Cross Keys, and Port Republic before withdrawing to help in the defense of Richmond.

Abraham Lincoln, frustrated by McClellan's lack of success, sent in Major General John Pope, but he was easily beaten back by Jackson. McClellan wrote to Abraham Lincoln, complaining that a lack of resources was making it impossible to defeat the Confederate forces. He also made it clear that he was unwilling to employ tactics that would result in heavy casualties. He claimed that "every poor fellow that is killed or wounded almost haunts me!"

On April 2, 1862, McClellan arrived with 100, 000 men at the southeastern tip of the peninsula. He took Yorktown after a month's siege but let its defenders escape. McClellan encountered the Confederate Army at Williamsburg on May 5. He was initially successful against the equally cautious General Joseph E. Johnston.

On May 31, Johnston's 41, 800 men counterattacked McClellan's slightly larger army at Fair Oaks, only 6 miles from Richmond. Johnston was badly wounded during the Battle of Fair Oaks, and the aggressive General Robert E. Lee replaced him as commander of the Army of Northern Virginia. The Union Army lost 5, 031 men, and the Confederate Army 6, 134.

McClellan had been unable to command the army personally because of a recurrence of malarial fever, but his subordinates were able to repel the attacks. Nevertheless, he received criticism from Washington for not counterattacking, which some believed could have opened the city of Richmond to capture. McClellan spent the next three weeks repositioning his troops and waiting for promised reinforcements, losing valuable time as Lee continued to strengthen Richmond's defenses.

McClellan maintained his estrangement from Abraham Lincoln by continuously calling for reinforcements. He also wrote a lengthy letter in which he proposed strategic and political guidance for the war, continuing his opposition to abolition as a tactic. He concluded by implying he should be restored as general in chief, but Lincoln named Major General Henry W. Halleck to that post without even informing McClellan.

A series of engagements known as the Seven Days' Battle took place, lasting from June 25 through July 1, 1862. On the second day, Union General Fitz-John Porter drove back a Confederate attack at Mechanicsville, 5 miles northeast of Richmond. Joined by Thomas Stonewall Jackson, the Confederate troops constantly attacked McClellan.

As Lee continued his offensive, McClellan played a passive role, taking no initiative and waiting for events to unfold. In a telegram to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, reporting on these events, McClellan blamed the Lincoln administration for his reversals. "If I save this army now, I tell you plainly I owe no thanks to you or to any other persons in Washington. You have done your best to sacrifice this army."

On June 27, a Confederate charge led by General John Bell Hood broke through the Union center at Gaines Mill. McClellan ordered the army to fall back toward the James River, where he would have the cover of Union gunboats. On July 2, after sharp rear guard actions at Savage's Station, Frayser's Farm, and Malvern Hill, the last engagement in the Seven Days' Battle, McClellan's troops reached Harrison's Landing and safety.

On July 1, 1862, McClellan and Lincoln met at Harrison's Landing, and McClellan once again insisted that the war should be waged against the Confederate Army and not slavery. Salmon P. Chase (Secretary of the Treasury), Edwin M. Stanton (Secretary of War) and vice president Hannibal Hamlin, who were all strong opponents of slavery, led the campaign to have McClellan sacked, but Lincoln decided to put McClellan in charge of all forces in the Washington area.

After General John Pope's defeat at Second Bull Run in August 1862, President Lincoln reluctantly returned to the man who had mended a broken army before. He realized that McClellan was a strong organizer and a skilled trainer of troops, able to recombine the units of Pope's army with the Army of the Potomac faster than anyone.

On September 2, 1862, Lincoln named McClellan to command "the fortifications of Washington, and all the troops for the defense of the capital." The appointment was controversial in the Cabinet, a majority of whom signed a petition declaring to the president "our deliberate opinion that, at this time, it is not safe to entrust to Major General McClellan the command of any Army of the United States."

The president admitted that it was like "curing the bite with the hair of the dog." But Lincoln told his secretary, John Hay, "We must use what tools we have. There is no man in the Army who can man these fortifications and lick these troops of ours into shape half as well as he. If he can't fight himself, he excels in making others ready to fight."

The Maryland Campaign

Northern fears of a continued offensive by General Robert E. Lee were realized when he launched his Maryland Campaign on September 4, 1862, hoping to arouse pro-Southern sympathy in the slave state of Maryland. McClellan's pursuit began on September 5. He marched toward Maryland with six of his reorganized corps, about 84, 000 men, leaving two corps behind to defend Washington.

Lee divided his forces into multiple columns, spread apart widely as he moved into Maryland. On September 10, 1862, he sent Stonewall Jackson to capture the Union Army garrison at Harper's Ferry,

and moved the rest of his troops toward Antietam Creek. This was a risky move for a smaller army, but Lee was counting on his knowledge of McClellan's temperament.

However, Little Mac soon received a miraculous stroke of luck. Union soldiers accidentally found a copy of Lee's orders, and delivered them to McClellan's headquarters in Frederick, Maryland, on September 13. Upon realizing the value of this discovery, McClellan threw up his arms and exclaimed, "Now I know what to do!" He waved the order at his old Army friend, Brigadier General John Gibbon, and said, "Here is a paper with which if I cannot whip Bobbie Lee, I will be willing to go home."

He telegraphed President Lincoln:

I have the whole rebel force in front of me, but I am confident, and no time shall be lost. I think Lee has made a gross mistake, and that he will be severely punished for it. I have all the plans of the rebels, and will catch them in their own trap if my men are equal to the emergency... Will send you trophies.

Despite this show of bravado, McClellan continued his cautious line. After telegraphing the president at noon on September 13, he ordered his units to set out for the South Mountain passes the following morning. The 18-hour of delay allowed Lee time to react, because he received intelligence from a Confederate sympathizer that McClellan knew of his plans.

The Union army reached Antietam Creek, to the east of Sharpsburg, on the evening of September 15. A planned attack on September 16 was put off because of early morning fog, allowing Lee to prepare his defenses with an army less than half the size of McClellan's.

On the morning of September 17, 1862, McClellan and Major General Ambrose Burnside attacked Lee at the Battle of Antietam. The Union Army had 75, 000 troops against 37, 000 Confederate soldiers. Although outnumbered, Lee committed his entire force, and held out until Ambrose Powell Hill arrived from Harper's Ferry with reinforcements.

Burnside's Bridge at Antietam

McClellan sent in less than three-quarters of his army, enabling Lee to fight the Federals to a standstill. During the night, both armies consolidated their lines. McClellan did not renew the assaults. In spite of crippling casualties, Lee continued to skirmish with McClellan throughout the 18th, while removing his wounded. After dark, Lee ordered the battered Army of Northern Virginia to withdraw into the Shenandoah Valley, and crossed the Potomac River, unhindered.

McClellan wired to Washington, "Our victory was complete. The enemy is driven back into Virginia." Yet there was obvious disappointment that McClellan had not crushed Lee, who was fighting with a smaller army with its back to the Potomac River. Lincoln was angry at McClellan because his superior forces had not pursued Lee across the Potomac.

The Beginning of the End

The Battle of Antietam was the single bloodiest day in American military history. Despite significant advantages in manpower, McClellan had been unable to concentrate his forces effectively, which meant that Lee was able to shift his defenders to parry each of three Union thrusts, launched separately and sequentially against the Confederate left, center, and finally the right.

Historian James M. McPherson has pointed out that the two corps McClellan kept in reserve were in fact larger than Lee's entire force. The reason for McClellan's reluctance was that, as in previous battles, he was convinced he was outnumbered. The battle was tactically inconclusive, although Lee technically was defeated because he withdrew first from the battlefield.

As with the decisive battles in the Seven Days, McClellan's headquarters were too far to the rear to allow him personal control over the battle. He made no use of his cavalry forces for reconnaissance, and didn't share his overall battle plans with his corps commanders. And he was far too willing to accept cautious advice about saving his reserves, such as when a significant breakthrough in the center of the Confederate line could have been exploited.

It was the most costly day of the war with the Union Army having 2, 108 killed, 9, 549 wounded and 753 missing. The Confederate Army had 2, 700 killed, 9, 024 wounded and 2, 000 missing. As a result of being unable to achieve a decisive victory at Antietam, Abraham Lincoln postponed the attempt to capture Richmond.

Lincoln and McClellan After Antietam

Here the gaunt figure of the Great Emancipator confronted General McClellan in his headquarters two weeks after Antietam. Brady's camera has preserved this remarkable occasion, the last time these two men met each other. "We spent some time on the battlefield and conversed fully on the state of affairs. He told me that he was satisfied with all that I had done, that he would stand by me. He parted from me with the utmost cordiality, " said General McClellan.

A few days later came the order from Washington to "cross the Potomac and give battle to the enemy or drive him South." However, McClellan refused to move, complaining that he needed fresh horses. Radical Republicans now began to openly question McClellan's loyalty.

Frustrated by McClellan's unwillingness to attack, Abraham Lincoln recalled him to Washington with the words: "My dear McClellan: If you don't want to use the Army I should like to borrow it for a while." On November 7, 1862, Lincoln removed McClellan from all commands and replaced him with Ambrose Burnside.

McClellan wrote to Ellen:

Those in whose judgment I rely tell me that I fought the battle splendidly, and that it was a masterpiece of art... I feel I have done all that can be asked in twice saving the country... I feel some little pride in having, with a beaten & demoralized army, defeated Lee so utterly... Well, one of these days history will, I trust, do me justice.

In October 1863, George B. McClellan openly declared his entrance into the political arena as a Democrat, and was nominated by the Democratic Party to run against Abraham Lincoln in the 1864 US presidential election. Following the example of Winfield Scott, he ran as a U.S. Army general still on active duty; he did not resign his commission until election day, November 8, 1864. In an attempt to obtain unity, Lincoln named a Southern Democrat, Andrew Johnson of Tennessee, as his running mate.

During the campaign, McClellan declared the war a failure and urged immediate efforts for a cessation of hostilities, with a view to an ultimate convention of the states, or other peaceable means, to the end that peace may be restored on the basis of the federal Union of the States. McClellan made it clear that he disliked slavery because it weakened the country but he opposed forcible abolition as an object of the war or a necessary condition of peace and reunion.

The deep division in the party, the unity of the Republicans, and the military successes by Union forces in the fall of 1864 doomed McClellan's candidacy. Lincoln won the election handily, with 212 Electoral College votes to 21 for McClellan, and a popular vote of 403, 000, or 55%. While McClellan was highly popular among the troops when he was commander, they voted for Lincoln over him by margins of 3-1 or higher. Lincoln's share of the vote in the Army of the Potomac was 70%.

After the 1864 election, McClellan set sail for Europe, and wrote to President Lincoln:

It would have been gratifying to me to have retired from the service with the knowledge that I still retained the approbation of your Excellency — as it is, I thank you for the confidence and kind feeling you once entertained for me, and which I am conscious of having justly forfeited...

In severing my official connection with your Excellency, I pray that God may bless you, and so direct your counsels that you may succeed in restoring to this distracted land the inestimable boon of peace, founded on the preservation of our Union and the mutual respect and sympathy of the now discordant and contending sections of our once happy country.

McClellan spent three years in Europe, returning to the US in 1867 to head the construction of a newly designed warship called the Stevens battery, a floating ironclad battery intended for harbor defense. McClellan, who lived with his family in Manhattan, rented an apartment in Hoboken, New Jersey, across the Hudson River from New York City. In 1869, the project ran out of money, McClellan resigned, and the ship was eventually sold for scrap metal.

In 1870, McClellan became chief engineer for the New York City Department of Docks, and built a second home on Orange Mountain, New Jersey. Evidently the position did not demand his full-time attention because, starting in 1872, he also served as the president of the Atlantic and Great Western Railroad.

After resigning this position in the spring of 1873, McClellan established Geo. B. McClellan & Co., Consulting Engineers & Accountants, and then left for a two-year trip through Europe, from 1873 to 1875. His essays on Europe were published in Scribner's, and his analyses of contemporary military issues in Harper's Monthly and The North American Review.

In 1877, the Democratic Party in New Jersey was divided into several contentious factions, producing a deadlock in the race for the gubernatorial nomination. At the state convention in early September, a delegate surprised many in the assembly by suggesting George McClellan. The response was enthusiastic, and he was nominated on the first ballot.

The general, who was attending dedication ceremonies for a Civil War memorial in Boston, had apparently expected his name to be presented, but had not anticipated receiving the nomination. He accepted the call and, still only 50 years of age, hoped that it would return him to public service. McClellan drew large, adoring crowds as he campaigned across the state, and won in November by almost 13, 000 votes. He served as governor of New Jersey from 1878 to 1881.

In late 1880, McClellan moved his family to Gramercy Park in Manhattan, two months before the expiration of his gubernatorial term, and commuted to Trenton to attend to the duties of office. Over the next few years, McClellan and his wife spent winters in New York City, Augusts at a resort in New Hampshire's White Mountains or Maine's Mount Desert Island, and the rest of each year in New Jersey.

McClellan's final years were devoted to traveling and writing. He justified his military career in McClellan's Own Story, published posthumously in 1887.

In 1884, George campaigned for Grover Cleveland, the Democratic presidential nominee. In early 1885, McClellan was expected to be named secretary of war in the Cleveland administration, but his candidacy was torpedoed by Senator John McPherson of New Jersey, a member of a Democratic faction that begrudged the general's gubernatorial nomination in 1877.

General George B. McClellan died unexpectedly at age 58 at Orange, New Jersey, after having suffered from chest pains for a few weeks. His final words, at 3 am were, "I feel easy now. Thank you." He is buried at Riverview Cemetery, Trenton, New Jersey.

Ellen Mary Marcy McClellan, although in poor health, outlived George. She died in 1915 in Nice, France, while visiting May at her home.

General George B. McClellan Statue

In front of Philadelphia City Hall

When this sad war is over we will all return to our homes, and feel that we can ask no higher honor than the proud consciousness that we belonged to the Army of the Potomac.

-General George B. McClellan

Abraham Lincoln, in a discussion with journalists about General George McClellan (March, 1863):

I do not, as some do, regard McClellan either as a traitor or an officer without capacity. He sometimes has bad counselors, but he is loyal, and he has some fine military qualities. I adhered to him after nearly all my constitutional advisers lost faith in him. But do you want to know when I gave him up? It was after the Battle of Antietam.

The Blue Ridge was then between our army and Lee's. I directed McClellan peremptorily to move on Richmond. It was eleven days before he crossed his first man over the Potomac; it was eleven days after that before he crossed the last man. Thus he was twenty-two days in passing the river at a much easier and more practicable ford than that where Lee crossed his entire army between dark one night and daylight the next morning. That was the last grain of sand which broke the camel's back. I relieved McClellan at once.

SOURCES

George McClellan

George B. McClellan

Ohio History Central

Peninsular Campaign

National Park Service

Heavy Victorian Father

All Quiet on the Hudson

1864: Lincoln v. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan

Mr. Lincoln and New York

General George B. McClellan

Enter George McClellan – Hero

Wikipedia: George B. McClellan

George B. McClellan (1826-1885)

Source: feedproxy.google.com

Irene Rucker Sheridan

Wife of Union General Philip Sheridan

Irene Rucker, born in 1853 at Fort Union, New Mexico, and spent all her life connected to the military. She was the daughter of Brigadier General Daniel H. Rucker, who was Quartermaster General of the US Army. Her mother, Flora McDonald Coodey, was the daughter of Joseph Coodey, a half-blood Cherokee, and granddaughter of Jane Ross, a sister of the celebrated Cherokee Chief John Ross. Joseph Coodey was a well to do citizen who owned and operated a grist mill on Bayou Menard near the crossing of the old stage coach road between Fort Gibson and Tahlequah. Irene spent most of her girlhood in Washington, DC, and at various Army posts.

Philip Henry Sheridan was born in Albany, New York, on March 6, 1831, but grew up in Ohio. He attended West Point and, after a one-year suspension for assaulting a fellow cadet with a bayonet. He fell only seven demerits short of being expelled, and finished 34th out of 49. Several other members of his class of 1853 also became well-known, including John Schofield, John Bell Hood, and James McPherson – first in the class of 1853.

Irene Rucker Sheridan

An obscure lieutenant serving in Oregon when the American Civil War began, Sheridan rose to the command of the Union's cavalry by the time the Confederacy surrendered. He saw action in Mississippi, Tennessee, Kentucky, and in Virginia, where his campaign through the Shenandoah Valley laid waste to an important source of Confederate supplies.

Sheridan started the Civil War as Chief Quartermaster of the Army of Southwest Missouri. Feeling that he would be a better field commander than a support officer, Little Phil, 5' 5" tall, persisted until he got an appointment as a colonel with the Second Michigan Volunteer Cavalry. A month later he commanded his first forces in combat.

At the Battle of Booneville, July 1, 1862, he held back several regiments of General James R. Chalmers' Cavalry. His actions so impressed his superiors that they promoted him to Brigadier General and assigned him command of the 11th Division, Third Corps, Army of the Ohio.

In the spring of 1862, just after Booneville, one of his fellow officers gave him the horse that he would ride throughout the war. At the time, the regiment was stationed at Rienzi, Mississippi, and Sheridan named the horse Rienzi. Sheridan was always able to control him by a firm hand and a few words. He was as cool and quiet under fire as any veteran trooper in the Cavalry Corps. At the battle of Cedar Creek, October 19, 1864, the name of the horse was changed to Winchester, the name of the town made famous during Sheridan's ride through the Shenandoah Valley.

On October 8, 1862, Sheridan again distinguished himself during the Battle of Perryville. He pushed two Arkansas brigades across Bull Run but was ordered back by Third Corps commander, Major General Charles Gilbert. Both sides suffered heavy casualties.

On December 31, 1862, the first day of the Battle of Murfreesboro, Sheridan held back the Confederate advance until his ammunition ran out and he was forced to withdraw. For his actions, he was promoted to Major General, and put in charge of the Second Division, 4th Corps, Army of the Cumberland. In six months, he had risen from captain to major general.

At the Battle of Chickamauga, September 19 and 20, 1863, Sheridan along with the rest of the army was forced to withdraw after two days of heavy losses. At the Battle of Missionary Ridge on November 25, 1863, Sheridan took the initiative and broke through the Confederate lines. General Ulysses S. Grant, newly promoted to be general-in-chief of all the Union armies, decided he wanted Sheridan when he went east.

Philip Henry Sheridan

By William F. Cogswell

In March, 1864, Grant assigned him to command the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac. During the Overland Campaign, Sheridan fought at the Battle of the Wilderness (May 5-7, 1864), and Spotsylvania Court House (May 8-21, 1864). From May 9-24, 1864, Grant sent him on a raid toward Richmond. The raid was less successful than hoped, although his soldiers killed CSA General J.E.B. Stuart at Yellow Tavern (May 11, 1864). Rejoining the Army of the Potomac, Sheridan's cavalry excelled at Haw's Shop (May 28, 1864), seized Cold Harbor (June 1-12, 1864) and withstood a number of assaults until reinforced.

Army of the Shenandoah

All during the war, the Confederacy sent armies out of Virginia through the Shenandoah Valley to threaten Washington, DC, and a raid throughout Maryland and Pennsylvania. CSA General Jubal Early attacked Union forces near Washington and raided several towns in Pennsylvania. In August 1864, General Grant organized the Army of the Shenandoah. He put Sheridan in charge to drive Early out of the Shenandoah and close it as a route to Washington.

Sheridan went at it with vigor. He beat Early at Third Winchester and Fisher's Hill. In the final battle, at Cedar Creek, Sheridan rallied the troops who were retreating after a surprise attack – Early was defeated. Sheridan ordered total destruction in the Shenandoah Valley – his troops destroyed crops and livestock, seized stores and equipment, and burned what they couldn't remove. Sheridan said, "If a crow wants to fly down the Shenandoah, he must carry his provisions with him."

The destruction presaged the scorched earth tactics of US General William Tecumseh Sherman's March to the Sea through Georgia – deny an army a base from which to operate and bring the effects of war home to the population supporting it.

Sheridan again joined the Army of the Potomac at Petersburg in March, 1865. At Waynesboro on March 2, he trapped the remainder of Early's army and 1500 soldiers surrendered. On April 1, he cut off CSA General Robert E. Lee's lines of support at Five Forks, forcing Lee to evacuate Petersburg.

President Abraham Lincoln sent General Grant a telegram on April 7, 1865: "General Sheridan says, 'If the thing is pressed, I think that Lee will surrender.' Let the thing be pressed." Sheridan wrote in his memoirs, "Feeling that the war was nearing its end, I desired my cavalry to be in at the death."

Sheridan's finest service of the Civil War was demonstrated during his relentless pursuit of Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, effectively managing the most crucial aspects of the Appomattox Campaign for General Grant. His aggressive and well-executed performance at the Battle of Sayler's Creek on April 6 effectively sealed the fate of Lee's army, capturing over 20% of his remaining men.

At Appomattox Court House, April 9, 1865, Sheridan blocked Lee's escape, forcing him to surrender later that day. After the surrender of Lee in Virginia and of General Joseph E. Johnston in North Carolina, the only significant Confederate field force remaining was in Texas, under General under Edmund Kirby Smith.

Sheridan was supposed to lead troops in the Grand Review of the Armies in Washington, DC, but Grant had appointed him commander of the Military District of the Southwest on May 17, 1865, six days before the parade. With orders to defeat Smith without delay and restore Texas and Louisiana to Union control, Sheridan headed south, but Smith surrendered before Sheridan reached New Orleans.

In March 1867, with Reconstruction barely started, Sheridan was appointed military governor of Texas and Louisiana. He severely limited voter registration for former Confederates, and then required that only registered voters (including black men) be eligible to serve on juries.

An inquiry into the deadly riot of 1866 implicated numerous local officials, and Sheridan dismissed the mayor of New Orleans, the Louisiana attorney general, and a district judge. He later removed Louisiana Governor James Wells, accusing him of being "a political trickster and a dishonest man." He also dismissed Texas Governor James Throckmorton, a former Confederate, for being an "impediment to the reconstruction of the State, " replacing him with the Republican who had lost to him in the previous election.

General Philip Henry Sheridan's Ride from Winchester

By Thure de Thulstrup

Sheridan had been feuding with President Andrew Johnson for months over interpretations of the Military Reconstruction Acts and voting rights issues, and within a month of the second firing, the president removed Sheridan, stating to an outraged General Grant that, "His rule has, in fact, been one of absolute tyranny, without references to the principles of our government or the nature of our free institutions."

Within six months, Sheridan succeeded William Tecumseh Sherman as commander of the Division of the Missouri, which encompassed the entire plains region from the Rocky Mountains to the Mississippi. There he immediately shaped a battle plan to crush Indian resistance on the southern plains. Following the tactics he had employed in Virginia, Sheridan sought to strike directly at the material basis of the Plains Indian nations.

Sheridan believed that attacking the Indians in their encampments during the winter would give him the element of surprise and take advantage of the scarce forage available for Indian mounts. He was unconcerned about the likelihood of high casualties among noncombatants, once remarking, "If a village is attacked and women and children killed, the responsibility is not with the soldiers but with the people whose crimes necessitated the attack."

The first demonstration of this strategy came in 1868, when three columns of troops under Sheridan converged on what is now northwestern Oklahoma to force the Kiowa, Comanche, Arapaho, and Cheyenne onto their reservations. The key engagement in this successful campaign was George Armstrong Custer's surprise attack on Black Kettle's village along the Washita, an attack that came at dawn after a forced march through a snowstorm.

Many historians now regard this victory as a massacre, since Black Kettle was a peaceful chief whose encampment was on reservation soil, but for Sheridan the attack served its purpose, helping to persuade other bands to give up their traditional way of life and move onto the reservations.

In March 1869, after Ulysses S. Grant became president and General Sherman became General of the Army, Sheridan was appointed lieutenant general with headquarters in Chicago. Returning to Chicago, he presided over the Great Chicago Fire of October 7-8, 1871. He brought troops into the city to stop looters and directed fire fighting and reconstruction. Although Sheridan's personal residence was spared, all of his professional and personal papers were destroyed.

While a bridesmaid at a wedding in Chicago, in 1874, Irene Rucker met General Sheridan, while his headquarters was there. Her father, General Daniel Rucker, Assistant Quartermaster United States Army, was on General Sheridan's staff. For the next few months, he courted her steadily, and contemporaries still recall the hero of the Civil War and "Miss Rucker riding down Wabash avenue in an open carriage."

On June 3, 1875, Irene Rucker married Philip Sheridan at the residence of her parents on Wabash Avenue in Chicago. She was a pretty brunette of 22; he was 44. The bride's dress was a white grosgrain silk softened by a tulle veil fastened with orange blossoms. The bride's accessories included a gold necklace with solitaire pendant, diamond solitaire earrings, and gold bracelets, all gifts of the bridegroom. General Sheridan and all the Army Officers appeared in full dress uniform.

After the wedding, the couple moved to Washington, DC, where they lived in a large house at Rhode Island Avenue and Seventeenth street N, bought for them by Chicago citizens who were grateful to General Sheridan for his work following the great Chicago fire in 1871. Irene quickly became one of the most popular members of Washington society, often entertaining as many as 300 callers a day. The Sheridans had four children: Mary, born in 1876; twin daughters, Irene and Louise, in 1877; and Philip, Jr., in 1880.

Sheridan Monument – Somerset, Ohio

In front of Perry County Courthouse

Sheridan refined his tactic of massive force directed in surprise attacks on Indian encampments, and mounted successful campaigns against the tribes of the southern plains in 1874-1875, and against those of the northern plains in 1876-1877, forcing them onto reservations with the tactics of total war. Although some of his generals in these campaigns, such as Nelson Miles, expressed a soldierly respect for the Indians they were fighting, Sheridan was notorious for his supposed declaration that "the only good Indian is a dead Indian, " which he steadfastly denied saying.

On November 1, 1883, Phil Sheridan succeeded William T. Sherman as Commanding General of the US Army, a position he held until shortly before his death. He was promoted to the rank of General of the Army of the United States by Act of Congress June 1, 1888, which is equivalent to a four-star general in the modern US Army. This is the nation's highest military office – which he achieved at the comparatively young age of fifty-two. He was the fourth man in US history to be so honored, the others being Washington, Grant, and Sherman.

In 1887, Sheridan had built a summer cottage in Nonquit, Massachusetts, overlooking Martha's Vineyard. The following year, he suffered a series of massive heart attacks, two months after sending his memoirs to the publisher. Although only 57 years old, hard living and hard campaigning and a lifelong love of good food and drink had taken their toll. Thin in his youth, he then weighed over 200 pounds.

General Philip Sheridan died August 5, 1888, at their vacation cottage, leaving Irene with four young children. His body was returned to Washington, DC, and lay in state at St. Matthew's Church until August 11, when he was laid to rest on a hillside facing the capital city near Arlington House, which helped elevate the Arlington National Cemetery to prominence.

General Philip Sheridan's Personal Memoirs (two volumes) were published soon after his death. Irene never remarried, saying, "would rather be the widow of Phil Sheridan than the wife of any man living." Curiously, Irene Rucker and his family are never mentioned in his memoirs.

Sheridan's famous horse Rienzi, renamed Winchester after it carried Sheridan on his desperate ride from there to Cedar Creek, was later stuffed and displayed at the Army museum on Governors Island in New York Harbor. In 1922, the museum was damaged by fire and it was decided that Winchester should be sent to the Smithsonian. The few remaining veterans of the city did not let Sheridan's war-horse leave without a fitting goodbye. They held a little goodbye ceremony, and the grandson of one of the veterans who attended read Thomas Buchanan Read's poem, Sheridan's Ride.

Fort Sheridan Centennial Legacy Statue

Depicts the General astride his mount Rienzi at the height of the Battle of Five Forks April, 1865.

A Time magazine article of May 1930 about Irene Sheridan stated:

Before the Senate last week came bill No. 319 to increase the pension of Irene Rucker Sheridan. Her present pension: $2, 500 per year. Proposed the bill: $5, 000. The Senate pensions committee recommendation: $3, 600. Up rose Colorado's Senator Phipps, a man of wealth and generosity, and said:

"The action of the committee reducing the amount is a mistake. Mrs. Sheridan is the widow of General Phil Sheridan who had a wonderful record. Mrs. Sheridan is well along in years and in all human probability, she will not enjoy the advantages of a pension for many years to come. I ask that the bill be approved in the original amount."

The Senate snubbed its pensions committee, and unanimously voted the widow of one of the nation's five generals $5, 000 per year. The bill must be acted upon by the House before she gets the money. Today Mrs. Sheridan, now living in retirement in Washington, is almost 80.

Since General Sheridan's death in 1888, Irene had divided her time between her home in Washington and the summer home in New England. She had not been active in Washington affairs since about the time of World War I. No one connected the wrinkled little old lady who gazed at Phil Sheridan's statue near her home with the great beauty of the 1870s.

Irene Rucker Sheridan died at her home at 2211 Massachusetts Avenue NW, Washington, DC, in 1936, at the age of 83. Funeral services were held in St. Matthew's Church, the same church in which Cardinal Gibbons performed the last rites for General Sheridan. Irene was survived by her three daughters, Mary, Irene, and Louise Sheridan, and two grandchildren, Carolina and Philip Sheridan III.

I don't usually make personal comments about the subjects of my posts, but this time I can't resist. While Sheridan was at times an able Civil War cavalry commander, he is one of my least favorite Civil War generals. First, because he had absolutely no regard for the lives of noncombatants. The second reason has to do with my Native American heritage. Regardless of his bigotry and carelessness, he seems to have had a wonderful wife.

SOURCES

Widow's Pension

Philip H. Sheridan

Scrappy Phil Sheridan

General Phil Sheridan

About Famous People

Irene Rucker Sheridan

General Daniel Henry Rucker

General Philip Henry Sheridan

Perry County Historical Society

Philip Henry Sheridan 1831 – 1888

Personal Memoirs of P. H. Sheridan

Source: feedproxy.google.com

4 Ways I Have Improved My Adsense Earnings

Grab my Free Adsense eBooks - here!If you want to monetize your website or blog, the great way to do it is through Adsense, those little ads from Google you see on many websites and blogs. There are lots of webmasters struggling hard to earn some good money through their sites while there are others enjoying hundreds of dollars a day from Adsense ads on their websites. What makes successful webmasters different from the other kind? They are using some smart techniques and they think out of the box. Like me, [...]

Source: on-line-tribune-internet-marketing.blogspot.com

Maria Louise Garland Longstreet

Wife of Confederate General James Longstreet

James Longstreet was born in Edgefield, South Carolina on January 8, 1821. His parent's names were James Longstreet and Mary Anne Dent. His father, who nicknamed him Pete, was a farmer, and Longstreet spent the first nine years engaged in farm work or outdoor activities with his older siblings William and Anna, as well as the four younger sisters he accumulated between 1822 and 1829.

His father owned slaves, and through the combined efforts of their toil and the family's work, the Longstreet farm was prosperous. Young James's early education was one gained through hard work, and he developed physical strength, independence of mind, and a strong work ethic.

While he dreamed of a military career, his parents recognized that entrance into West Point Military Academy would require preliminary academic training. On October 7, 1830, young Longstreet was removed from the rural life he loved, and sent to the Augusta, Georgia, home of his uncle, noted attorney Augustus B. Longstreet, where he enrolled at the prestigious Richmond County Academy.

General James Longstreet

A sociable young man, James gained several friends whom he would retain throughout his adult life: one of these was a young man named Ulysses Simpson Grant, who was in the class behind James. At the time he graduated from West Point as part of the class of 1842, he ranked 54th in a class of 56, sixteen of whom would go on to be Civil War generals.